At the end of the 2000 reenactment season, I didn't think I had anything else to say about the hobby and it was my plan to try my hand at fiction, with a story about John Henry, the little rag doll who can talk. I struggled for about five years with a story centered at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas where John performs heroics with members of Holmes Brigade. I had a nice beginning, a strong middle, but I couldn't figure how to conclude the story.

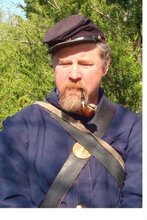

In the meantime, I still attended reenactments and jotted down some thoughts and observations on a web site blog. With the publication of Chin Music volumes one and two, my friends naturally assumed there would a volume three. I dodged the demands as best I could thinking I no longer had it in me to tackle another book. In November 2009 I became a grandfather. While a joy, it presented some challenges. Layna was born with cerebral palsy and requires a special kind of attention.

During the winter of 2014, I decided to edit volumes one and two and make them available as ebooks. The first edition of volume one is still available on Amazon in paperback format, but with volume two, I've lost contact with the publisher. Publishing in book form requires some advance funding, which I don't have right now. Ebook publishing is simpler and requires no payment.

CHIN MUSIC FROM A GREYHOUND

OF

THE CONFESSIONS OF A CIVIL WAR REENACTOR

VOL.3

The rest of the story

THE LAST BATTLE

At the turn of the 21st century, with all eyes

looking forward to the September reenactment at Lexington, Missouri, John Maki

announced that it would be the last one ever held. Every three years, as long as I can remember,

the State Historic site had hosted the battle weekend on the original site

where a Masonic College and the old Anderson House stood. Also known as the Battle of the Hemp Bales, I

saw my first Lexington reenactment here in June 1978.

I was attending Central Missouri State University in Warrensburg

and had just started taking a class on Civil War History, taught by Dr. Leslie

Anders. As explained in greater detail

in Volume One, Dr. Anders introduced me to the love of Civil War history and put

me on this road I am on today, 37 years later.

If I had not seen the flyer on the History Department bulletin board for

this Lexington battle reenactment, the worm would have turned in a different

direction.

There had been a remembrance of the mid-September 1861 battle of

Lexington since the 1950’s or perhaps earlier.

Photographs and home movies show soldiers from the nearby military

academy running around the field in either homemade uniforms or army issue

khakis, firing M-1 Garand rifles. In some instances, original equipment might

have been used.

Over the years, since 1978, the battle reenactments that I’ve

participated in have gotten bigger and more spectacular drawing several

hundreds of reenactors and thousands of spectators. Unfortunately, the park is too small to hold

all those bodies, so the decision was made, by the State, to cancel the

reenactments here. It was with a bitter

heart that John Maki told us that September 2000 would be the last ever held.

In the past, I had always portrayed a Union soldier, serving

with Holmes Brigade. The last couple of

outings, at least one day out of the weekend, I had donned civilian clothing

and served on the other side as a member of the Macon County Silver Greys. This

was a group created by Dave Bennett and is mentioned in greater detail in volume

two.

For this weekend, the Silver Greys, about 50 of us, were camped

on the grounds of the Victorian home of Greg Hildreth and Amy Heaven. This home was featured in the 1999 motion

picture Ride with the Devil, the Tobey Maguire, Civil War on the Western Border

epic.

Not sure exactly the order of business during the weekend, but

at some point that early Saturday morning, the Greys marched away from Greg and

Amy’s house and walked north on 13Hwy, which is the main drag towards the town

square. We may have veered off towards a

lake side park or not and I may have this reenactment confused with a

previous.

A big shindig was planned on the square near the old courthouse

where hundreds of townspeople congregated to hear fancy words and speechifying

mixed with food and beverage vendors.

There were also folks on hand to sell or distribute historical

pamphlets. Not sure if there was a

parade or what part the reenactors played during these festivities, but with a

saloon nearby, my guess is the boys spent most of the day getting corned. I

think Sunday was reserved for the battle reenactment.

On that hallowed day, the Silver Greys were massed in a line

near the back porch of the Anderson House facing east. Before us, the ground

rose slightly in elevation, and then tapered off to a flat area of some

distance. In the original battle, the Federals occupied the flat area with trench

works dug in a semi-circle. Artillery

pieces were in strategic positions to help with the foot soldiers. But despite this superiority in firepower,

the southern lads continued to deny the Federals access to the river and

drinking water during this hot siege.

Using movable breastworks made from hemp bales, the southern lads were

able to advance under hot fire and eventually forced the Federals to surrender.

Our hemp bales were constructed by lashing two straw bales tightly

together. At least ten rolling

breastworks were in our hands. We were

simply waiting for the cue to advance.

About a stone’s throw to the south of the Anderson House stands

the Visitors Center, a modern building housing battle relics and memorabilia

from the 1861 battle. At the time of the

fight, the Anderson’s had a garden and a summer kitchen located to the east. The summer kitchen survived the battle but was

lost some years after the Civil War and was never rebuilt. The garden had been replanted in an area

fifty yards square with an unknown variety of herbs, vegetables, and whatnots

growing. There was also a fruit orchard

of limited number but not sure what grew from its branches.

While the main part of the reenactment would be going on to our

northeast on an area of flat open ground, our little action was considered a

sideshow. Though a small part of the big

picture, John Maki had placed us here because we were the most authentic and he

knew we would not do anything goofy. John had recently been hired by the State

as a caretaker of sorts to a couple historical sites in the region. Working at historical sites was a dream come

true. A dependable guy with some clout,

John definitely had a voice when it came to suggesting which people the State would

invite to their historical site to shoot black powder. No more bozos on this bus.

While hundreds of Federals were on hand for this reenactment, we

were not sure who we would face for our part in this comic opera. Smiles brightened the faces of all the boys as

we saw the familiar faces of Holmes Brigade pop up over the brow of the

hill. They had come to torment us. We cheered and playfully taunted each other

across that short distance of less than one hundred yards.

Some guys hiked their trousers down and bared shiny bottoms,

while others began hurling the rotted fruit that had fallen from the tree. Soon it was a regular game between the two

sides with spoiled fruit arching back and forth between the lines in a volume

that nearly masked out the sun. The hemp

bales were our only protection as the stuff smacked it with a putrid explosion

of thick syrupy goo. When several of the

projectiles landed nearby undamaged, more than one fool hardy lad left the

protection of the bale to recover it and hurl it back. We were like ducks in a shooting gallery as

we dare not stick our heads up. Plus the Holmes Brigade had the advantage of being

able to throw downhill. Only the lad

with the strongest arm on our side could hope to reach his target throwing

uphill.

Mike Gosser was Captain of Holmes Brigade at this time and he

stood right in the middle of the front line wearing the most God awful Hardee

hat decorated with the biggest snow white ostrich plume I ever saw. “A silver dollar to the man that knocks that

chicken off his hat,” came the shout from one of the wags as the projectile

throwing intensified.

Play was interrupted by the firing of a cannon. This signified that the reenactment for real

had started. Rotted fruits and

vegetables were dropped from our hands and muskets, rifles, and shotguns were

picked up. But the playful taunts and insults continued as the lads challenged

the manhood and/or firing abilities of each other.

“You can’t hit me, you beat.”

“Is you an old man or old woman?” “I’ve

seen better heads on a boil!”

Guns roared and at the same time we manhandled those bales

forward a few yards at a time. It was a

struggle to move them uphill as they were big square blocks weighing over three

hundred pounds each. Push the bale on the top until it crashed flat then dig

fingers into the bottom and flip it up.

It took two or three volunteers to maneuver each bale while everyone

else provided the firepower against the foe.

After nearly an hour, we had pushed, prodded, and cursed those

bales to within spitting distance of Holmes Brigade. It had been hot work and the Silver Greys had

worked up a sweat. At this time, we

thought we’d get to jump into the Federal trenches and wrestle with the boys of

Holmes, but play was halted because it was time for the Federal surrender. What a disappointment. We didn’t even get to shake hands or pat each

other on the back. The Federals were

herded away by other pukes while Missouri Governor-in-exile Claiborne Fox Jackson

said some words praising the Missouri boys and damning the blue coated

enemy. History states the Federals were

given an immediate parole on the spot and set free, unarmed of course.

Pilot Knob Sept 2014

At the 150th battle reenactment of Pilot Knob, MO., the boys of Holmes Brigade camped Friday night on the courthouse lawn of the Iron County courthouse in Ironton, MO. The soldiers of the 14th Iowa were here prior to the battle, in 1864, which culminated at the fight at Fort Davidson, some two miles north. For the last couple of times Holmes Brigade has been coming to Pilot Knob, we have been allowed the privilege of camping here.

It has been the habit for the boys to pull up in the parking lot, throw a gum blanket down on the lawn and nap. Come first light, we would march into the fort or the surrounding state park area where the balance of reenactors camped. I would be in error in saying only Holmes Brigade was invited to camp on the courthouse lawn. Since Holmes Brigade was the host unit, we could invite another authentic unit or units to camp with us, if they so desired. I think well over a hundred boys showed up at the Ironton courthouse.

Traditionally, Friday night is dedicated to the sport of drinking. Beer of all makes, rum, hard cider, whiskey, you name it. With the sun barely on the horizon, corks and beer tabs are popped and contents poured down the gullet. This type of adult diversion usually continued until the pangs of hunger compelled the lads to seek a civilized restaurant. Once the stomach was satisfied, a return to the jug was sought til sometime in the wee hours prior to dawn. Nothing has changed in the last 35 years except our waist line and our hair line.

On this historic night of 2014, the 150th anniversary of the battle at Pilot Knob, some old and familiar faces returned, as if ghosts from the past. Dickson Stauffer, that kindly old gentleman, the first captain of Holmes Brigade, and a true historian in his own right, rode to the event with us, in the party van. Dave Sullivan, from Grand Island, Nebraska, Jack Buschman, from Colorado, Mark Olson, from Independence, Missouri, and me, made up the passenger list. Aaron drove most of the way. In Columbia, Missouri we picked up Dickson.

There was a shout sometime near midnight as a vehicle came and deposited old buddy Jon Isaacson. I last saw Jon at the last Pilot Knob, either 4 or 5 years ago. At that time he was beginning to make a name for himself on the country/western stage in Nashville heading a group calling themselves Ike Jonson and his Roadhouse Rangers. Jon was the lead singer in this country swing tribute band. Rhinestone cowboys with wide brim hats. From clips I heard on the Internet, Jon was quite a soulful singer and could warble and croon like the classic cowboy singers of yesteryear.

As stated earlier, hunger pangs soon called and several of the boys decided to call on the local eatery. Hig and I climbed into Jon Isaacsons car and within a short drive; we arrived at a BBQ just outside the town of Pilot Knob. We ordered a beer and chow, and parked ourselves at a table while on a small stage, a trio belted out some folk music. In the Ozarks, youd expect to hear a lot of hillbilly music, but not a Peter, Paul, and Mary tribute band.

About 8 AM, all the federal boys formed up in lines ready to prepare to move out. Hardtack and an apple were issued to each man to suffice for breakfast. We probably lolly-gagged and played grab-ass too long preparatory to moving out, because within a short time, someone spotted the johnnies coming up the road south of town. A temporary truce was declared to allow us to get our ass into gear.

At least three companies or over one hundred of us Federals took the long hike up Shepherds Mountain. Almost four miles, as the crow flies, this route of march took us up a nearly 45 degree rocky incline to an elevation of about 600-800 feet. Twists and turns all the way up, with pebbles the size of grapefruits. Not one straight path up and down like a mad roller coaster. Though a bona fide hiking trail, armed soldiers had not traversed the mountain in 150 years.

At the crest, the pesky greybacks started annoying us with pot shots. We replied in kind, and all the way to the bottom of mountain, we had a fire and fall back retreat. At the conclusion, which lasted from about 10 am till 1:30 pm, we were dogged tired. Though grumbling during the march was the norm, I'd say we were all in good spirits and everyone accepted the challenge with pride. A few laggards, with real medical issues where attended to by Medical Steward, Michael Whitehead. Several of us almost threw in the towel, but comrades-you know who you are- were able to lift the moral of the rest with humor and song. Though the climb up and over the mountain was tough, with many sore feet, it was worth the price of admission and a source of pride for those who took the challenge. The mountain hike was a Holmes Brigade scripted adventure, which was planned almost a year in advance.

From the journal of the 14th Kansas Enrolled Militia April 5, 2009 It was a crisp and windy early spring day. Our detachment had been sent into Clay County, Missouri to confirm an illegal and unlawful assembly in the township of Shoal Creek. It was rumored that a group of pro-southern agitators was stirring up the populace with anti-government speeches. Upon entering the town, we found a crowd of old men, women, and children assembled near the square. The people seemed spellbound or perhaps hypnotized by the sharp serpent's tongues of three overly dressed and red-faced gentlemen. It seems the men took turns speaking to the crowd. As soon as one fellow got out of breath, another agitator would jump in and continue the sermon. Upon seeing our arrival, the pro-southern agitators got even more excited, waving their arms like pinwheels and shouted for the crowd to resist the Northern invasion. After so much preaching, the crowd had a glazed look in their eyes, as if they'd been sniffing paint fumes too long. "Beware the devils in blue uniform," one fat-faced agitator spat," the vile damn Kansans will burn your homes, ravage your women, and eat your children." The spittle flew from his lips like morning rain. Our captain, a veteran of war with Mexico and with the Plains Indian, calmly announced that the assembly was illegal and must be disbanded at once. He warned that arrest was the alternative. Someone in the crowd shouted some nonsense about the Constitution and freedom of speech and some other silliness, but our captain would have no room for debate. At a command, our company fixed bayonets and stepped forward. As expected, the townspeople scattered like frightened sheep. In the confusion, a few citizens suffered some bruising and broken bones. Women fainted and children bawled. But not one Federal soldier was molested. The three agitators were arrested and thrown into the local jail and the town was placed under martial law. Within the hour, another detachment of Kansas militia came in and between the two of us; we had the town pretty well bottled up. No one could leave or enter the town except with a written pass. . All roads were guarded and anyone traveling was subject to having their belongings searched. A few of the more foolhardy tried to sneak out of town by taking to the woods. These Rebel sympathizers were hunted down and were given a rough treatment when our boys found them. . Later in the day, some guerrillas attempted to bushwhack our boys that were gathered at the mill. A skirmish line was thrown out and a brisk gun battle went on for a brief time. One or two of our boys were mortally wounded and some others suffered broken bones as the result of pistol balls. The guerrillas tried to drive us out of town but we were too well armed and all good shots. That evening we could hear the wild hogs having supper. Pity the poor lad who met an untimely fate all because he fell under the spell of anti-Lincoln gibberish. I must end this page of my journal because it's my turn to interrogate the wounded prisoner.

Winter Encampment, Lexington, Missouri Feb. 2006

When the Union Army halted its campaigning between December and March, the soldiers built winter quarters for themselves. In many cases they were simple one-room log cabins small enough for the comfort of two to four men, or one grown dog. These structures were built with a wood floor, a crude fireplace and a canvas roof. There is a large field on the southern end of Lexington town, near the Victorian home of Amy Heaven (the house was in the film, RIDE WITH THE DEVIL). In fact, she owns this huge tract of pasture land, and in the past, has allowed horses to graze and the Frontier Brigade to camp. Near the western edge of this pasture stands a one-room cabin, measuring about 30 foot by 40 foot, built from split logs and clay, complete with a good size fireplace. In mid-January, Aaron Racine proposed that an encampment could be had on this field. The original goal of this encampment was to do manual labor, which included cutting down trees, clearing away brush, digging pits, and assembling huts. On February 4-5, 2006, about two dozen brave (or should I say foolhardy) souls braved chilly temperatures for the first "BUILD A CABIN" days, just like the old boys did it nearly 150 years ago. Without a doubt, we all thought the greatest reward lay in just getting out of the house after a long hibernation. Many of us hadn't seen each other since Athens, so there was much gaiety and laughter throughout the day. John Maki had assembled his "little house on the prairie" beginning the previous Wednesday. He cheated a little bit. He used all the power tools in his shop to neatly chisel all the log pieces. It resembled an old fashioned out house and had about as much room inside. The Kip Lindberg/Dave Bennett team brought a pre-fabricated doghouse. One can only imagine Snoopy lying on top. There were four walls, covered on the inside with bathroom wallpaper. All that was required of the team was to dig a foundation, about three feet deep, by seven foot square. Then, like a jigsaw puzzle, the team fitted the walls together, added a shelter tent roof, and PRESTO! They had to crawl on their hands and knees to get through the special dog door and into their beds. They even had a small stove inside; about half the size of a shoe box I believe. The men who made up Team Higginbotham had no pre-fabricated or pre-cut pieces of housing. They went right to the source and began attacking 6-inch thick trees with long handled axes, cross cut saws, hatchets, sweat, and brute strength. Hig, Dave Bears, Steve Hall, and Shane Seley each took turns with the hand tools. After a pretty good notch had been sliced in the timber, a couple of fat people pushed and pulled on the tree until it fell with a thud. Six-foot sections were cut off each fallen tree until enough were on hand like so many Lincoln Logs in a child's toy set. Then came the stacking and criss-crossing until by mid-afternoon, there was a foundation about two-foot high. For Team Higginbotham, their log hut will require several more visits until complete. At mid-day, John Maki had a fine dinner cooked up of beans and ham, plus a loyal citizen had provided a loaf of delicious cinnamon bread for our dining enjoyment. Provost Captain Abraham Comingo (Ralph Monaco) arrived to administer the loyalty oath to some recently paroled Rebel scarecrows. He also read articles from an old 1863 newspaper, filled the air with political rhetoric and smoked several vile cigars at the same time. Sometime after lunch, we were surprised by about a dozen guerrillas in captured Federal uniforms. They appeared on horseback, standing atop a rise in the hillside, and then they came bolting towards us at a trot, pistols popping in each fist. Quickly, we assembled and were prepared to return fire, but were again surprised to discover we had another enemy on our flank. This was six or seven guerrillas on foot. They crashed through the tangle of woods behind us and 'pop pop popped' at us with large caliber revolvers.

After a heated five-minute skirmish, a truce was called. The scarecrows crawled out of the woods, like so many ticks, and commenced to 'hee-haw' about how they had surprised us. In all fairness, we all thought something might be brewing when Captain Tom and Aaron Racine told us to have our weapons and accouterments where we could reach them. I believe they got the news of graybacks in the area from a spy. As the day turned toward evening time, we shrugged on our greatcoats and began a migration to the big log cabin and its fireplace. Despite the growing cold temperatures, Aaron supplied the evening refreshment when he brought in two 2-gallon casks of German lager. I think he also had a bottle of OLD OVERCOAT, but not sure. Meanwhile, Gregg Higginbotham held the audience captive with his tall tales from the past. He spoke about the tailgate romance he witnessed at Gettysburg '88, the adventures of the Waffle boys at Raymond, MS, the romance of Roger Forsyth, and other saucy adventures. Each story was punctuated with the famous Higginbotham body language and sound effects. After the 4 gallons of German lager had been sucked dry, it was time to go into Lexington town for even more popskull and a bite at the sports bar. This was about 7:30 PM. In the restaurant we had hot chow, washed down with a Rolling Rock or a Black and Tan. One of the Rebel scarecrows, from earlier in the day, was in the bar with us and tried to get us excited about a reenactment in northern Missouri where you can fire up to 300 rounds. Aaron's rebuttal was priceless. Hig merely said, "I'd rather jack!" By about 9:30, we returned to Tiny Town, with the intent to get some shut-eye. Overnight, temperatures plunged like Pam Anderson's neckline. I shared the bungalow with John Maki. During the wee hours of the morning, John gave me an extra blanket, but I still felt as if my feet were turning into blocks of ice. Team Kip Lindberg spent all night in their hut feeding the tiny shoebox stove with bits of wood. I think they had some fagots in the hut with them. In the darkness, Kip was whacking on these fagots with his hatchet, so they'd be able to fit in the stove, when he accidentally brought the hatchet came down on his thigh. He asked Dave Bennett to take him the hospital. His cut, though not serious, required eight stitches. The boys who spent the night in the big 30x40-foot cabin spent just as miserable a night as the rest of us. The cabin had many gaps between the logs and the wind whistled through as if it was a pipe organ. I think Ralph slept in his car, but Aaron, Captain Tom, Hig, and a few others were shivering like Mohammed Ali. Even though the fireplace was crackling, it did little to take the chill out of the drafty room. Hig told me he spent a sleepless night sitting upright in a chair with his feet in the fireplace. About 5:30 AM, I staggered into the cabin, to warm up. Even though everyone was wrapped up like mummies, it didn't appear as if they'd slept. I told Captain Tom that if we do another winter encampment, let's do it in June. Hig and John Maki had to be at the 1859 Jail in Independence by 7:30 AM for a Jim Beckner motion picture. I road down with Hig, plus I had no desire to stay another day, so I packed up my belongings and said goodbye to the wretched survivors of the WINTER ENCAMPMENT of 2006. And that's all I have to say about that. THE END.

"The Dutchmen of the 3rd Missouri" Approximately 16 men from Holmes Brigade attended the event at Carthage, Missouri May 3-4, 2003. We wore the grayshirts! The rest of the Federal infantry battalion, another 4 companies of Kansans and Nebraskans, came with sack coats and sky blue trousers. They kind of looked at us funny, not knowing who we were supposed to be. Many of the MSG troops were scratching their heads trying to figure us out as well. It seems that in the original 1861 battle, only the Federal artillery wore dark blue issue uniforms. Both the Third and the Fifth Missouri Infantry wore a type of gray overshirt. Just before the battle Saturday, we were treated to the sight of one of the "Hood" daughters displaying the National colors under her skirt. Soon a lengthy artillery duel between at least ten full-scale guns developed. This was followed by the infantry fight in which we crossed and recrossed "Buck's Branch", exchanging withering volleys with the enemy, then formed a square and "skedaddled." On Sunday, we came in from the opposite side of the field. This was to be a 2 PM fight, so we had to form up at 1:15 and stand around and fan our balls till kick off time. We marched up a paved road and delivered a volley into the backsides of the Missouri State Guard pukes that'd stacked arms and were "coffee cooling." They immediately crapped their pants, grabbed their weapons and began to return fire. By this time, we were entering the field from the right and extended our 5 companies in a battalion front. A light rain was falling off and on. The field was somewhat muddy as we slowly pushed the sesech back across "Buck's Branch". I was reloading after a third volley, and yanked the tail of the paper cartridge between my two front teeth. Twenty years ago, I had a front tooth capped. When I yanked on that cartridge, my tooth went with it, flying somewhere in the tall brush. I said something using off color language and showed my gaped tooth smile to Gregg Higginbotham and John Maki. They said I looked like a "Jack O Lantern", or better yet, a hillbilly in a Branson Musical Show. It didnt hurt because in 1976. I'd had a root canal, with a cap put on the dead stump. Anyway, I felt embarrassed and stupid, but I continued on. We were pushing the sesech pukes across the stream. Cavalry was running around the outer edges of the battlefield with pistols popping, while infantry grappled like tag team wrestlers. Action was going on in different parts of the field by individual units of men like it was a three-ring circus, minus the high wire act. Ground charges hurled potting soil high into the air or vomited geysers of water from the stream. At one point, "Herr Siegel" ordered us Gray Shirts across Buck's Branch to flank a company of MSG. Mike Metcalf lost his footing while crossing the muddy bank and landed on his back, staining his gray shirt with wet mud. The rest of us had mud clinging to our trousers up to our knees, elbows, and brims of our hats. Plus we had wet grass stains from diving on the ground to escape a sesech volley, as well as black powder residue on our hands and lips. Jim Beckner, whom we all called "Gross Oohpaw" or Great Grandfather, was struck down by enemy balls several times, as was Hig and Maki, but "Herr Siegel" came along and resurrected them on the spot, saying, "You all are no longer dead, so get back in line!" While the fight raged on, some confusion was evident as battle lines overlapped. One MSG commander roared at Hig and Maki to "get back over here and into line." He was another one of those confused souls who was ignorant of the clothing we wore and couldnt understand why we were on that side of the field thinking we were some of his boys. We corrected him on the spot with several well-aimed musket volleys. I fired 40 rounds, missing front tooth and all, and we slowly forced the enemy from the field in what was scripted as a generic battle. We marched off the field, triumphantly, between ranks of cheering spectators singing, "Mary had a little Lamb." A few of the other Federals tried to sing "Marching through Georgia", but they were hushed up. . As we were about to be dismissed, "Herr Siegel" congratulated us all on a fine job. Both he and the battalion commander had big grins. As we took stock of ourselves at the end of the event, we looked like wed fallen off the manure wagon into a hog pen. We were only looking for one thing after this knock down fight, however, lager beer! If this event is held again, in a couple years, it is hoped we can get more boys into Gray Shirts and possibly educate some on what the correct impression should be for an 1861 event.

After Action Report of 2004 Franklin, TN event

We pulled into Federal registration between 10:30 and 11AM where folks behind the table asked for "papers please!" A medallion was handed out plus a cheesy pinup poster featuring two soldiers, a US guy and a CS guy. We were instructed to "drive down along the fence line about a half mile, then turn left for another half mile," to find the US camp. I was the only one dressed out in blue, but Robbie Maupin and Dan Hadley (both who would be on the CS side) agreed to see me to my camp. We drove past scores of Union soldiers, but when pressed for directions to the digs of the Western Brigade, they said, "On down the road." We drove past a red barn-a strip of yellow police tape wrapped all the way around it to keep the reenactors out. Past a few more "Yankees," then at the bottom of the slope stood one solitary A frame tent. Clustered around the canvas shelter I recognized Captain Terry Forsyth and Lt. Tom Sprague right off. I got my stuff unloaded and set on the ground. Mark Olson came from out of the A and we all hugged on each other. As I looked around I only counted seven Holmes Brigade boys. Including Capt. Terry and Lt. Tom, there was Corporal Dave, Mark Olson, Gary Riley, Greg Wait, and myself. Where was everyone else? Terry thought some more boys would be coming in throughout the day and possibly into Saturday morning. He was about half right. Later that afternoon, three more Holmes Brigade boys arrived. Charles Hoskins, and John and Sam Peterson. The very first words out of John Peterson's mouth were "way the fuck down here in the last camp!" We now had ten men in our company! We were really looking pretty sad as a unit. It was said we might have to consolidate with another company. Then when spirits were at its lowest, we received 6 new recruits. Four were from a Pennsylvania group and two were from the 1st Colorado. I think they were orphans like us and needed a home, so they wandered into our nest. They all looked well fed, like little butterballs. One had been an officer back east, plus two others were sergeants and still wore the rank on their sleeves. The PA boys chitter-chattered like schoolgirls the entire afternoon, until we took off on our long march, then they bitched because "everyone is walking so fast" and they couldn't keep up. "That's how Western soldiers march," I explained with a grin. Our first skirmish was up the road a short distance. It was midafternoon, I guess. After going up the narrow dirt lane, we were commanded to drop our knapsacks in a pile. Oh, I forgot to mention this, but we'd be going to another campsite after this here skirmish. So, if there was something you had to have that night-like a blanket-you had to lug it with you now! So, we dropped packs and reformed the battalion. We were the eighth company of the battalion and the colonel tended to remind us "y'all are the end of the line!" We couldn't allow the enemy to flank us, was the implication. The colonel, a little bantam roster with white chin whiskers, croaked out the order to advance in line of battle. "Guide to the colors!" The Stars and Stripes were smack dab in the center of our battalion. When the order is given to guide or dress to the center, all the boys look to the center, or where Old Glory is. The men in the ranks attempt to march in a straight line, although officers and NCO's will bellow to "Get the bow out of the line!" or "Dress to the center!" You also have to maintain a touch of elbow with the guy next to you otherwise the ranks will look sloppy, resembling less an army and more a mob. The fighting was going hot and heavy now. Cannons roared somewhere off on our far right. Confederate cannons were several hundred yards to our front spitting smoke. A line of dirty Confederate soldiers dotted the landscape in front of these guns. Their line stretched from horizon to horizon. About one hundred yards separated us from them. The little colonel shouted at us the fire as a battalion, then by company, then by file, then finally at will. A Sergeant Major ran rings around all of us. He carried a staff like a drum major. His job was to echo the orders from the colonel. During the crash and boom, the voice of the little colonel could not be heard, but the Sergeant Major barked like a lion. Plus Captain Terry and Lt. Tom were on hand to repeat stuff as they heard them. It was not unusual to have ten or twelve people shout the same order, in case you didn't hear it. We might have been better served if we'd had cue cards to read and react to. After about 30 rounds had been smoked through my Springfield, I noticed the cone becoming fouled. I tried to worm the crud out with a nipple pick, but it would not budge. The battle petered out about five minutes later and was halted. We were ordered to snap caps, but I told the colonel my cone was fouled, so a few minutes later I was putting on a new one. I have two extra cones in my cartridge box. We got to sit down for a bit after this fight and several of us nibbled on snacks from the haversack while a volunteer gathered canteen's from all around and went to fill them. All too soon, a drum sounded and shouted orders came to reform the battalion. Once again in ranks, we marched off a distance of about a half-mile to Rippavilla plantation. This was an old antebellum house that was on property owned by the Saturn automobile company. The grounds around Rippavilla were neatly manicured, like a golf course, and surrounded by a white picket fence. The entire battle reenactment was on Saturn property. I don't know how many acres they had, but they must have sold a lot of cars to buy up all this land. The actual town of Franklin was about ten miles north. The battle reenactment site was close to a town called Spring Hill. We took another break here, because just ahead was the highway. State troopers would shut down the right hand lane of this highway so we could march up about another half-mile, over pavement, to reach the place where we would camp for the night. The entire time we were on our feet, going from one place to the next, the Pennsylvania boys continuously belly ached that "everyone is walking so fast," or "what's everyone's hurry?" Considering we were the last company in an eight-company battalion and these boys were in the last rank of that company, I can't understand why they couldn't keep up. Nevertheless, they complained the whole trip. I stated, as a matter-of-fact, "we are all Western soldiers and that's how we march." They weren't the only complainers in the Union army. Quite a number of well-fed and aged men lay off to the side of the road during the long hike. Most gasped and puffed like beached whales and sucked on canteens while a pard nursed their pulled hamstrings or sore ankles. I didn't have too much trouble myself. I'm proud that I was able to hoof it with the rest of the boys with no ill effects-other than I was dog-tired when we finally stopped and my shirt was wringing wet. Where we pulled up for the night was in the middle of a God forsaken old cornfield, stripped bare of nearly all vegetation. Right down the center of this field was a trench line that was waist deep and at least 200 hundred yards long. All us Union boys were obliged to bed down here, so muskets were stacked, campfires started, and bedrolls were laid out. We had barely settled in, when word came that four men from each company would have to go out on night patrol. That is they would sit out in the dark and watch to see if the enemy would try to sneak over. The Pennsylvania boys quickly volunteered out of our small company-good riddance. So the night rangers marched off into the darkness and the rest of us stretched out under the stars. I brought out my big slab of bacon from my haversack and started cutting off small hunks to fry in my tiny little skillet, while Mark began boiling coffee. A finer supper I never had! The early October evening was slightly cool, but not uncomfortable. Several of us snuggled close to the small fire, however, and gazed hypnotically at the cracking embers or up into the starlit heavens until sleep overcame us. Before falling asleep, I saw the headlights of at least a dozen vehicles coming through our area bringing artillery. Sure enough, in the full light of morning, there were ten or twelve cannon positioned on our right and on our left all along that 200-yard trench line. Reveille came to us at an early hour; the eastern sky was just barely beginning to lighten. Dim figures began to move around in the pre-dawn darkness rolling up bedrolls and stirring the embers of a dying fire in order to coax coffee into boiling. This ritual had barely been completed, when a slight rain drizzle began to fall. Those that had ponchos, drug them out. However, within five minutes the rain had petered out. It seems our sentries had been out all night, exchanging pleasantries with Johnny Reb no doubt. As they wandered in from their all night frolic, it seems that brought news of the enemy, who was just over past the hedgerow-one hundred yards to our front. Thanks for stirring up a hornet's nest, I thought. Word came to us to form battalion, right face, and forward march at a left oblique away from the comfort of the muddy trench to a worn path that wound through the aforementioned vegetation. We'd left our packs and haversacks behind and hoped our comrades would not pilfer while we were gone. My observation on this was made as I came to the conclusion that only four companies of the Western Battalion were on this prowl. "Where are the rest of the boys?" I said aloud even as we stepped through the other side of the hedgerow into a wall of butternut and gray. Looked like the whole Reb army only fifty yards in front of us. Shock and awe hit the face of our little colonel as he realized the trap, but with unflappable presence of mind, he ordered us to let loose with a few aimed volleys, then back we skedaddled-back through the hedgerow in the direction of the trench. We had barely collected ourselves back on the "friendly side" of the hedgerow when it was noticed that, in our absences, the entire Union Army had got up out of the trench and was hotly engaged with a foe just as equal in number on our left. Now I knew what had happened to our support. They'd gotten stuck in a trap themselves! I believe a few more volleys were fired, and then we all backed up till we fell into the trench works. It was while the boys were taking stock of themselves after the little tussle with Johnny Reb, that we noticed that a boy from our very own "eighth" company was in trouble. This was the guy from Colorado. Come to find out, his knee had popped and he was writhing on the ground in some discomfort. Some pards went out into no man's land, got on both sides of him and half dragged/carried him back to our side. After a brief conference between officers and NCO's of the battalion, it was decided an ambulance needed to be called in. At any reenactment, large or small, a medical crew is always on call. Whenever guns go off and men run around in hot wool clothing in the summer time, an accident is bound to happen. Most generally these fall in the category of ankle sprains, blisters, or heat exhaustion. Whenever something like this happens, or worse, a uniformed staff officer will either summon help via a walkie-talkie or dispatch a mounted soldier to locate an emergency vehicle. As I have stated before, safety is job one at any reenactment. When a real injury occurs, play is halted! Both side's cease-fire and stand at ease until the emergency vehicle has arrived and the poor victim is hauled away to the local hospital or nearby dressing station. Once the emergency vehicle has left the area, then play is resumed. On this morning at Franklin, I had already seen a number of lame and fagged out boys during the march from our original camp to these trenches. Over the next couple of hours, the call for medical attention would continue. I know for a fact one boy either fell off his horse or got kicked by it, plus there was a few more cases of pulled, twisted, or sprained limbs. In our "eighth" company alone, there would be three more casualties before the noon hour. Once the ambulance pulled away, with our comrade "Colorado" strapped on a stretcher, play was to be resumed. However, for some odd reason, our battalion was obligated to trot to the opposite end of the trench line. We had to march at the double quick a full one hundred yards or better, while another battalion took our spot. I wanted to get at least another forty rounds out of my knapsack, so I handed my musket to Lieutenant Sprague. Just has I turned my back, the battalion took off a trot. I caught up with the boys after a moment, retrieved my musket, and resumed my place in the rear rank. All too soon we were ordered to commence firing at a solid wall of butternut and gray. Already, boys were packed in the trench like sardines, so the rest of us stood on the back lip of the trench, firing over their heads. It was hot work for a spell until the Rebels advanced towards us with a fierce yell. They looked like a thousand snarling uncaged beasts. Within a moment, they'd poured into the trench works and it was a hand-to-hand match with a lot of pushing, shoving, growling, and gnashing of teeth. I remember jumping on the back on one Confederate, as he clambered over the trench, and then his pard jumped on me. Our section of the trench works seemed to be the only spot where the Confederates had broken through. Play again was halted; the end of Round Two. The southern trespassers were obligated to rejoin their pards on the opposite side. The rest of the southern horde had stopped short about ten yards from the earthworks and seemed content to hurl insults at us. As we all regrouped and took stock of ourselves, I walked up the line to see if I could spot Dan Hadley and Rob Maupin. Like I said, the Confederate legions were just on the other side of the trench line from us-no more than ten yards away making recognition easy. Sure enough, I saw both of them, in another battalion to our right. I took off my hat and hollered, "Hallo" at them. Dan hurdled the trench works in one bound, like a gazelle or an Olympic athlete, and gave me a big bear hug. I quickly noticed that his butternut clothing was filthy. In fact both men looked like they'd rolled around in the mud or fallen in a manure pile. Hell, I was somewhat of a dirty little man myself! While Dan treated me like a kissing cousin in his embrace, he told me that he and Rob wanted to leave the event that afternoon. They had talked to Susan and Linda. The girls wanted to visit the Carter House on Sunday. I said that'd be all right. We'd be able to shower, eat in a sit down restaurant, sleep in a soft bed, and then sight see the next day. I agreed to meet both Dan and Rob at the WIDE-AWAKE tent, on sutlers row, at sundown. The WIDE-AWAKE Video Company was filming a documentary/reenactment video of this event. After another warm embrace, Dan leaped back to the other side of the trench. After this second round of shooting had concluded, we had a lengthy pause, which lasted about one hour. During that time, we were told to gather our knapsacks and move them one hundred yards to the rear. It was about this time that I heard our own company had suffered more losses. Acting First Sergeant Charles Hoskins had suffered an asthma attack, Lt. Tom Sprague had some complications with bad food he'd eaten, and our beloved Captain Terry Forsyth became lame when the nails of his boots went up into his feet. Both officers "cut stick", located their automobile, and returned to Missouri within the hour. I never saw them leave, not did I get a chance to say goodbye. We'd already lost Colorado and I never saw the Pennsylvania boy's again that day. We were back down to seven- Mark Olson, Corporal Dave, Gary Riley, Greg Wait, John and Sam Peterson, and me. We'd become orphans and were obligated to fall in with another group of guys. The company that adopted us welcomed us by placing us at the end of the line-as if we had leprosy. While we all shuffled from one foot to the next waiting for the next order of business, Olson and I decided to go after so water. Near where we'd placed our knapsacks was a huge stainless tanker truck holding fresh water. Standing in two lines behind the truck was a whole bunch of Confederate butternuts. As Mark and I walked up to join the line, I noticed there was at least another hundred butternut scarecrows sitting on the ground, "coffee coolin", including an old Crowley's Clay County pard, Clayton Murphy. While Clayton and I exchanged pleasantries, Mark had spied Dan Hadley and Rob Maupin some distance ahead. The two were trying to get water from a dog dish or maybe it was a birdbath. While we all waited in line for water and grab-assed, play on the battlefield had resumed. Cannon roared and muskets flamed 200 yards behind us. As calmly as spectators, we merely glanced over our shoulder at the spectacle, but no one felt like relinquishing their place in the water line just to blow more cartridges. Most of us figured there were enough bodies down there to fight, or as one person declared, "Right now, we're on break, we're off the clock!" What was odd was there were only a half dozen of us Yankees in the mob of graybacks. We were all after a cool drink of water, so it was like being off the time clock. Eventually, it was my turn at the fire hose. Every drop of water was precious, so a 55-gallon drum caught the excess drips from the spigots. I'll never forget this young woman was standing by the spigot, bitching and complaining that she'd been out here all by herself. She obviously was part of the water department that donated the fresh water and she was complaining about working past her shift. I remember she was an attractive gal, but very self-absorbed. I got my water and joined Olson, Hadley, and Maupin by the birdbath. After declaring again about meeting at the WIDE-AWAKE at sundown, Mark and I rejoined the battle. "Back on the time clock," I declared to Mark as we found our weapons

Saturday, August 9, 2008

Stand of Colors After Action Report

As you will soon discover as you read this, the Civil War event held May 17-18, 2008, in Kansas City, Mo., known as Stand of Colors, was filled with colorful moments. More than any other event in recent memory, and too many new to campaigning in the deep woods, there loomed an element of danger and risk to health. It began when the sponsor asked reenactors to register in one place then park their cars five miles away in another place and take the school bus into camp. The registration was only a half-mile from the event site, yet reenactors and spectators alike were told that parking was at the old abandoned Bannister Mall in Kansas City. Bannister Mall had been closed for almost a decade due to poor attendance and because it was located in a high crime area. However, the sponsor said there would be 24-hour security at the Mall provided by Kansas City finest boys in blue. After registering, you could go into the event site and drop your stuff off. But then they depended on you to voluntarily leave, drive north five miles, park at the old abandoned shopping mall, hop on the school bus, then come all the way back. B.S.! I rode to Stand of Colors with Mark Olson and it was his decision to park behind sutler row. You see all the sutlers were NOT required to park at the mall. Row after row of cars about 50 yards behind sutler row, so Mark squeezed his vehicle in with the rest. It was after 7PM so it was hoped no one would pay attention. Let me state right of the bat that Stand of Colors was a mainstream event, with a little campaigning done by a few groups (I was in one such group, as I will illustrate). Being a mainstream event, these meant spectators would be wandering about looking at stuff. That meant there had to be refreshments on hand to satisfy their thirst and hunger. Soft drinks, funnel cakes, battle burgers, beer, and a souvenir stand-selling Stand of Colors T-shirts. At 7PM on a Friday night however, none of these vendors were open. I had eaten prior to leaving home, but Mark had not. His stomach was growling so we drove out of the event to Jess and Jim's Steak House on 135th and Holmes-just about a mile away (as the crow flies). On the way out we met another pard, Eric Jackson, who was also hungry so the three of us went in the high-class eatery-we had our Yankee clothes on, but no one seemed to mind. As we would discover, there were other reenactors, who'd had the same idea as us, which was to 'farb out' one last meal before the event actually kicked off. Mark had a $25 steak and Eric had a $10 hamburger. I wasn't that hungry but I had an $8 salad and washed it down with two draught beers. We all had two beers apiece. It was close to 9PM when we got back to the event site. There was still a bit of sunshine to guide out steps to the Federal camp. We would quickly discover this was NOT our home for the night. We'd decided to go for the 'campaigner experience' this event, so we played follow the leader as a guide led us about a quarter-mile along a path deep in the woods. We left the comfort of the Federal Cavalry camp (which was our rallying or starting point) and entered a wild tangle of wilderness. About one hundred yards later, we came out the other side into a clearing. Actually this was a firebreak about fifty yards wide extending one-mile end to end. Here was placed some of the all-important power lines. A few paces and we met a fellow coming out of a small clearing. This clearing was only about 20 yards square but it would be our home for the night. This fellow had just sprayed the area with a garlic smelling concoction that he claimed would put creepy crawlies into dreamland. HA! I think the ticks were wearing gas masks. We also had to be wary of poison ivy. It grew in abundance. Once we'd located home for the night, bedrolls were laid out with some of the guys already falling into dreamland. I resolved to boil some coffee before calling it a night. There was still a sliver of light on the horizon. It wasn't total dark yet. There was a fire already started. A four-man cavalry patrol occupied a piece of nearby real estate. Their nags were tethered nearby. Within 30 minutes, I had coffee boiling in my peach can. I shared some of this witches brew with some pards and then it was to sleep. It got cold that night and most of us slept only in spells. Sometime during the night, Aaron Racine and Ralph Monaco arrived in camp. Aaron was our Lieutenant, while Ralph came with the impression of Provost Marshall for the District of Western Missouri holding the rank of Captain. I don't know what time it was when the 1st Sgt. hollered for us to get up. The sun wasn't even awake! It might have been around 5 AM. We had just enough time to boil some coffee, nibble on a piece of hardtack, and get our bedding and knapsacks secure, when the call came to form up. It seems another battalion was in a pickle and needed our help. The johnnies were surprise early risers and decided to test Federal pickets watching the firebreak on our left. A few sporadic pops developed into a fourth of July spectacular of noise. A johnny battalion or two was inching their way down the firebreak. The Federal's were formed in a line behind some fallen timber. Our battalion was in reserve, but the Colonel told our Captain Sprague to peel off to the left onto a trail. By parking our small company on this trail, we were protecting the left flank in case of a surprise move by the enemy. Our ruse worked. The enemy did not try to take our flank because we were positioned as a speed bump. We did wave at each other, but that was it. The two main groups, the Federals and Confederates, traded a couple volleys back and forth for a spell. Finally, the Confederates blinked. They turned about face and away they went. After this episode, the entire Federal group, us included, went up the firebreak in pursuit of the foe. I think the colonel placed us in reserve where we sat on our butts while the rest of the boys in blue scraped for a brief spell. . Once again we watched as the johnnies fell back under the might of the boys in blue. They fell back a full two hundred yards and out of sight behind the roll of the land. During this time, with our battalion still in reserve, Mark Olson made the remark that he had a check for Jay Stevens. Mark is Holmes Brigade treasurer and Jay Stevens made some hardtack for us. Only problem was Jay was with the Tater Mess and on the johnny side. No problem says Ralph, aka Provost Marshall. All by himself, Ralph advanced on the enemy with drawn pistol and calmly announced to the Confederate division, "that they were under arrest." We'll never see Ralph again; say's some of the men. Ten minutes later, up pops Ralph with 4 Confederate prisoners. These are members of the Tater Mess including Jay Stevens himself. Now we are all friends with the Taters. We've worked hand in hand with them at many Missouri events and also on the Wide Awake film, Bad Blood. We've shared beer and laughs over the years. So it was we all shared a big wide grin and a laugh as Ralph brought them into our laps so Mark could hand Jay his check. We hee-hawed and pressed the flesh for a couple minutes until the Colonel told us we had to go back to Friday night's hole in the woods. Our company trudged down the firebreak to our hole and dropped knapsacks. It was probably 7 AM. In this hole in the wilderness was a supply of 6 five-gallon containers of drinking water. This was the entire supply for the battalion. We were ordered to return here to guard this vital supply. END PART ONE PART TWO I neglected to mention that from 6AM to NOON-with the exception of one hour-we had to carry our knapsacks with us. We would have preferred NOT to carry those 50lb. suitcases on our backs the whole morning, but the Colonel said, 'once we leave the area, we may not come back.' In my knapsack I had 60 additional rounds, a toothbrush, tobacco, an extra shirt, my blanket roll, one drug issue containing antibiotics, vitamin pills, pep pills, sleeping pills, tranquilizer pills, one miniature combination Confederate phrase book and Bible, one hundred dollars in Confederate script, one hundred dollars in greenbacks, nine packs of chewing gum, one issue of prophylactics, three lipsticks, three pair of nylon stockings, and one pair of dry socks. Shoot a fellow could have a pretty good time in Westport with that loot and I didn't want the ticks to carry it off. Sorry, couldn't resist using a line from the classic motion picture, Dr. Strangelove. Of course I didn't have three lipsticks. It was chapstick. So we were as loaded down as pack mules when we had our first scrimmage with the enemy (the fight in the firebreak, as mentioned in part one). After this adventure and Ralph Monaco's hilarious single-handed capture of a Confederate Division, our 33 man company returned to last night's bivouac (in hindsight, we could have left those back breaking knapsacks behind. Oh, well). At the conclusion of Part One, I told you we were guarding 6 five-gallon canisters of drinking water. This was the only source of cool, clear water for a quarter-mile. If the johnnies had known that 33 men were babysitting the water supply of the whole Union Army, do you think they might have launched a raid? Perhaps they feared the ticks more than us wee few. With nothing better to do for nearly an hour, we dropped our 50lb. suitcases from our aching backs and flopped on our backsides. Some boys gnawed on worm castles while others began the first in a series of tick hunts. Trouser legs were rolled up or trousers were completely lowered in search for the source of that annoying itch. A few of the boys raised their shirts up and took turns picking the vermin off each other. Looked like monkeys grooming each other I thought. For me, now was not the time to worry. I'd sprayed my lower legs with OFF with 100% DEET. I also had some BURTS BEES insect tonic that I sprinkled in my hair and beard like pomade. But since my wife is a nurse at the local hospital, I calmly announced that I'd let her work me over with a fine toothcomb when I returned home Sunday afternoon. We might have lain in the clearing- last night's bivouac- for almost an hour, maybe less, when our Captain told us we had to relieve the boys of the 1st and 2nd Minnesota who'd been on picket all morning. It was only about 8AM so the question that needs to be asked is, how long had the Minnesota boys been on picket? Rather than grumble, we picked ourselves off the tick invested carpet of greenery and shouldered our knapsacks for a trek westward. Once again we were told that we probably would not come back to this same oasis, so it was knapsacks on. About a quarter-mile we followed a narrow twisting deer path through even more horrible wilderness, through tall grass, over stream beds, and up muddy embankments. After some huffing and puffing, we drew up to a stop and gathered around another small oasis. Ahead was the rearguard of the 1st Minnesota, about 5 boys I think. The main body was occupying two positions one hundred yards apart at the edge a firebreak as similar as one we had experienced earlier. Lieutenant Aaron Racine and second platoon occupied one end of the flank and Captain Tom Sprague took first platoon up the rise to cover the other flank. By positioning themselves in this way, they could see about quarter-mile in either direction. Any enemy movements would either have to come down the firebreak, which even a blind man could detect, or they'd have to come through a wagon road. This road was on the opposite end of the firebreak, about fifty yards away. Both platoons had an eye on this avenue as well as the flanks. After all us boys had settled in, the reconstituted 1st and 2nd Minnesota came marching past, heading back the way we had come up. Once they got to the oasis, I suppose they would all flop on their backsides, tilt their hats over their eyes, and catch a few Z's. The Colonel told us that if we get into any trouble, the Minnesota boys would come to the rescue. 'But try not to get into any trouble for a while, ok. Let's hope the johnnies don't try any shenanigans' I was with three other lads on escort duty guarding the chap who carried the National Colors. If there was so much as a whisper of the enemy in the area, we had orders to escort the colors to the rear. While 1st and 2nd platoons lay out in the morning sun working on their tans, the color escort boys sought shade. I remember puffing on my pipe and then gnawing on a chicken leg during this intermission. As I lay under this very unusual tree, I happened to notice several unusual growths dangling from the branches. The growths, about the size of a walnut, were shriveled, wrinkled and had little tufts of fuzz on them. Call me daffy, but I swear that they looked like little shrunken heads. I considered collecting several so Steve Hall could examine them. Steve has been practicing phrenology for a number of years and is very skilled at interpreting lumps and bumps on heads. He prefers to read the bumps on a female noggin. It's probably how he met his fiancée. Just as I reached out to snag one of 'the heads' for my haversack, I felt a queer sensation crawl up my backside. It might have been a tick making a nest in my nether regions, but it caused me to reconsider. I didn't want no Mummy's curse to haunt me so I lift the bizarre ornaments alone and resumed gnawing my chicken leg. Aaron Racine and 2nd platoon was on the other side of the tree line and only a chicken leg's throw away, so I threw my chicken leg at them. It landed right in the middle of that pile of boys and a couple of them jerked like they'd been bushwhacked. I giggled only for an instant, because my laughter was drowned out by a sudden hurricane of noise. Attack! ! Peeking out and up to the top of the hill, I saw that Captain Tom Sprague and 1st platoon had formed a skirmish line, from tree line to tree line, and was hotly engaged with at least 300 scarecrows! Within seconds, Aaron Racine had formed his own platoon of men, advanced up the hill at the double quick, and the two forces formed a duet of death against these monsters under Sterling Price. Only for a moment could I remain an audience to this titanic struggle of good versus evil. The colors and the guard were quickly ordered to the rear. Before turning away, I could see the unclean denizens of doom were continuing forward; the puny attempts by of our boys in blue only an annoyance. The scarecrows of Price's army seemed to be walking forward with a shuffle and with a loose limb swagger that reminded me of zombies advancing in search of brains to eat. Atop that vision of doom, my blood nearly froze as a high pitched screeching came from the lips of this mob. Imagine a long tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs. It was the Rebel yell! When word had first come of the attack, Sgt. Dave Sullivan had been ordered to hot foot it to the rear to bring up the Minnesota boys. He had run like a gazelle, a quarter of a mile back to our original oasis. But the Minnesota boys had heard the fireworks and were in fact streaming to the rescue. When informed of the dire situation, our colonel seemed more bored than alarmed. 'For Pete's sake! What are those rascals up to now?' Meanwhile, the enemy had poor Captain Tom and his gallant lads boxed in a corner and it certainly looked like the end for my pards. Where was I? In the rear with the gear. Then the Colonel burst upon the arena with drawn saber and 100 ticked off (no pun intended) Minnesota boys hot on his heels. The two opponents collided with such a force. It was like a wave crashing onto the rocks. Though they had us outnumbered 3 to 1, Price's scarecrows were the first to turn tail and slithered back up the hill. We had successfully defended the narrow gateway to the Union rear and the vital water supply. I say we, although I did little except offer encouragement. I dare not dirty my musket in this game because my job was to defend the flag. In fact I was prepared to sacrifice myself in case an unclean Rebel hand dared touch it. Thankfully the color guard was many yards away from the fighting so the opportunity never came up to for me to become a martyr for the Union. I'm afraid I've wagged my tongue far too long on too many minor details, so I'll make a long story short by saying that between 10AM and noon we were engaged two more times with the enemy. However these episodes were minor in detail and only involved a dozen scarecrows creeping about in the woods. With a few pot shots of our own thrown in the mix, the threat once again to the vital gateway and the path to the Union rear was thwarted. The minor episodes on our area did not involve the entire Union and Confederate armies. There were flash points of activity throughout the entire 4-mile square event site. Somewhere there were artillery duels and elsewhere cavalry clashed. And in other remote parts of this park, small sized infantry units butted heads in skirmish lines or sniped at each from the cover of heavy timber, brush piles, or drainage ditches. Every participant was engaged in some kind of situation under arms and to some degree out of sight of the public. The public battle was to be at 1PM. Between noon and one we spent the time getting in position, forming ranks, and sucking on ice chips. Two men, properly attired as field hospital orderlies, came by carrying a stretcher between them. On this canvas stretcher was a gum blanket. Under this gum blanket was a bag of ice. As the men advanced past the ranks, they handed out a few ice chips to each man. Some guys put the ice in their cups while most put it in their hats to cool off their boiling brains. This procedure took some time as there were about 100 of us including the Minnesota boys. You see it was barely noon and the temp was already in the upper eighties or lower nineties. The way I recall the battle was our battalion would be joined by three other Federal units all arriving from different parts of the field. The colonel said we had the smallest battalion so we would be used as skirmishers covering the entire front of the Grand Division. Until this moment I didn't know we had a Division of Federals nor did I know we had a Brigadier General. At one point this dashing figure came galloping up on horseback and said some words to our colonel (who was dismounted the entire weekend, I forgot to add). The colonel said everyone would drop knapsacks for the fighting, then singled out the color guard, five of us including the flag bearer, and said we would hide out under a big shade tree and out of sight of the public. When they, the skirmish line, came past, we would pop up and join the line and then we could unfurl the flag. That was all right by me. I had no desire to dirty my musket or get my clothes soiled by flopping in the tall, tick infested weeds as a skirmisher. So the battalion went one way, in a skirmish line about a quarter-mile long, and the color guard waited under the shade of a big evergreen tree. Tagging along with us was Captain Abrahm Comingo aka Ralph Monaco. He was puffing on a big cheroot and occasionally sipped on some medicinal brandy he had in a flask. He generously offered my pards and me a nip as we waited for the big show to catch up to us. Under this big shade tree we had to watch where we sat because poison ivy grew here and loved the shade. Ticks and poison ivy were the two most annoying things we had to deal with. We had passed the bottle back and forth only a few times when the artillery opened up somewhere to our far right. This was followed a moment later by the sound of many muskets pop-pop-popping. This developed into a perfect thunderstorm of noise from all quarters as it singled the opening of this battle for the public. The public was about a half mile away so they couldn't see this opening act; just a lot of smoke, noise and tiny ant like figures. Within a few minutes, the battle would get even closer to them, until at just at the final act, we'd be almost in their laps. For the amusement or comfort of the paying spectators, which was $15 a head, a set of bleachers was set up. Those that could not or would not sit in the bleachers were welcome to park themselves in an area of freshly mown grass about 50 yards by 20 yards. Signs were placed saying that the front was for blanket sitters, the second row for lawn chair sitters, and the third row for those who preferred to stand. Anyway, let me get on with the battle. The skirmish line slowly fell back until they came past our shade tree. That's when we jumped up and joined the ranks. The colonel shouted for the men to form companies, so we sought Captain Tom and the boys. They occupied part of the line and the color guard was placed on their left. Pretty soon here come some of those Minnesota boys who formed up on my left. I think we moved some other companies around until we looked about evenly balanced with the colors right in the middle. After this the General came trotting up on his horse and told the colonel that our battalion will form on the right of another battalion. So we marched ahead some paces, did some fancy wheeling, guided left, and hooked on with another battalion. They also had a set of National Colors. I believe there were four more big battalions of Federals milling around about a hundred yards apart. And they each had a big set of National Colors also! I'd wager we had 500 Federal Infantry, plus about 75 horse soldiers running about popping pistols and swinging cavalry sabers. Not sure of the total amount of artillery for our side but maybe ten is a good number. Now the Rebs had not been napping the whole time we were doing our fancy movements and alignments. I counted three huge lines of scarecrows, each measuring a quarter-mile in length each. I don't recall any Army of Northern Virginia soldiers. No gray uniforms that I could see except for the mounted officers. I think all the foot sore soldiers of Sterling Price's army wore some type of civilian garb or butternut. Also, I don't recall if the Stars and Bars were carried. I think I saw a Missouri State Flag and one that is blue with a white cross (can't think what that is). So the lines of both armies stood some yards apart, glaring at each other, taunting each other with curses and unclean suggestions. All the time we were firing up and down the line, firing by file, firing by companies, firing at will. Sometimes a man would fall, but the colonel said not to take too many hits just yet. There came a time when a portion of the Grand Division advanced a few paces or did an about face a fell back a few paces. The scarecrows did not scare easy this day. The advanced two paces, fell back one, then advanced five paces, and fell back two. We fell back five paces, advanced one. You see we were losing the day. By this time the armies were within spitting distance of the line of spectators. They could smell our gun smoke and our sweat. A few better placed volleys, and then word came that we would retreat. Finally the colonel gave us the order to run away in panic. Men began to stumble and fall, but most broke ranks and streamed for the rear. The colonel pretended to try to stop us. 'Rally, boys. No run away. No stop, you cowards. Keep up the panic.' The entire Grand Division had fallen to the rear in various forms of disarray. The Rebs continued to advance and pop at our yellow backsides. By this time, the colonel had succeeded in reforming our battered battalion for one last hurrah. I was on the left of the guy carrying the colors. I remember twisting on my right heel and stared at him with a puzzled look of bewilderment, then my musket slipped from my grasp, and I collapsed like a bag of moldy potato peelings. The Rebs continued to advance, they passed over my dead body, and a few moments later, the fight was declared over, and the horn of resurrection was sounded. About two hundred boys, of both persuasions, lay on this field as dead, dying, or wounded. I think costumed hospital stewards scurried about for a few minutes before we all were allowed to get up. I vaguely recall hearing the roar of applause coming from the bleachers. I hope the people got their $15 worth of entertainment. For my pards and me, it was time to visit the beer garden. We stacked muskets, placed our knapsacks and stuff by the stack, and took only a tin cup and a wallet to the oasis of barley and hops.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008