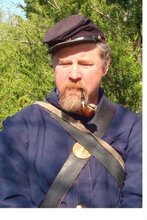

I've been in the hobby of Civil War Reenacting for 28 years. Yes, that kinda makes me an old fart. The first time I went to Prairie Grove, Arkansas was October 1980. The original battle was fought on December 7, 1862. Since 1980, a reenactment is held on the State Historic Site every two years, as close to the anniversary weekend as possible. Those who attend the Civil War Reenactment at Prairie Grove, Arkansas come from faraway places like: Missouri, Kansas, Mississippi, Texas, Colorado, Nebraska, Louisiana, Oklahoma, as well as within the state of Arkansas itself. In 2008, we actually had someone who came from Idaho.

No could tell what the weather would be like during early December. Be that as it may, every two years, from 1980 to 1998, I would join several hundred reenactors on this hallowed ground and share a weekend either basking in an Indian summer or freezing in sleet or snow. One always came to Prairie Grove expecting the best, but preparing for the worst; in weather that is.

1998 was the last time I came to Prairie Grove, Arkansas until this year. Why I waited 10 years to return to this event I can't say. Some years I would go to the Fort Scott, Kansas for their Living History/Christmas program, other times the weather seemed too hazardous to risk travel. Whatever the excuse, I resolved that in 2008 I would return.

John Maki came by to pick me up just before noon on Friday, December 5th. I had taken a vacation day for Friday and the following Monday. John was the company cook for our group, the Holmes Brigade, and the back of his truck was loaded with boxes, two coffee pots, two wedge tents, tent poles, skillets, nesting tins (galvanized steel buckets that could be stacked like the popular Russian nesting dolls-one into another). In the wooden boxes he had slab bacon, sausage, onions, potatoes, coffee, cooking utensils, and other miscellaneous sundry items relative to cooking, camping, and tenting.

I had a knapsack, weapon, traps, and a burlap gunnysack with my uniform and extra blankets. John and I had about 5 blankets apiece, plus mittens, greatcoats, and fur hats. Mine was made from a Jack Rabbit while John's was made from muskrat.

We arrived at the State Historic Site in Prairie Grove, Arkansas after about a four and a half-hour drive. Like I mentioned earlier, it had been ten years since my last visit. During that time, a lot of construction had taken place and many more business lined the road running from the exit off 71Hwy to here. I recall in the past only a few businesses including a liquor store, a convenience store, a motel/restaurant, and a redneck bar called Club West. Now there were dozens of strip malls, grocery chains, drive-thru banks, and gas stations where once stood desolation. I was happy to see the redneck bar was still where it used to be, but the name had been changed (don't recall what it goes by now).

In weeks and months before the Battle of Prairie Grove, the Union Army of the Frontier, under General John M. Schofield, had sent his three division to harass Confederate forces, under Thomas C. Hindman, all up and down western Arkansas, from Bentonville to Ft. Smith. I will not bore you with a history lesson. The fall 2004 issue of BLUE AND GRAY magazine has an interesting and lengthy article on the campaign leading up to and including the December 7, 1862 battle of Prairie Grove.

This harassment led to several engagements between the Blue and Gray forces and at one point, feeling isolated and fearing a major counteroffensive, First Division, under General James G. Blunt called for reinforcements. The Third Division of the Army of the Frontier, commanded by 25-year old Francis J. Herron, had been in Springfield, Missouri since early November, but on December 3, 1862, they left the city and began a forced march that would cover 100 miles in three and a half days.

No tents or extra baggage accompanied Herron’s men, but as the modern 21st century man is much older and more full figured than our forefather’s were, we made camp with wedge tents and wool blankets.

Maki and I arrived at the Prairie Grove Battlefield State Historic State Park about 4:30 PM Friday evening. Before the sun had disappeared, we had our tent up, beds made, clothing changed, and a fire roaring. We even had coffee boiling and even had time to fry some slab bacon Maki had brought from Alma, MO. Reenactors continued to come in throughout the night and into Saturday morning. Friday evening I met MYSPACE buddy, Jimmy, who came to Prairie Grove with the Eighth Kansas. Jimmy shared a cup of coffee with me and then he introduced me to his pards. The members of Holmes Brigade and the Eighth Kansas would merge with other companies to form the Federal Frontier battalion that would operate that weekend.

With the crack of dawn came the shrill bugle cry of reveille. It was a very cold morning until the sun warmed things up. The high was expected to be about 50, but in those early hours, it was colder than a landlord’s heart. At this chilly hour, the enemy would have no trouble finding us.

Bundled up in greatcoats, scarves, mittens, and fur hats, every Billy Yank hovered over small cook fires, drank scalding black coffee from tin cups, gazed hypnotically at the flames and watched bacon sizzle in a hot skillet with eyes glazed over from lack of sleep. Reenactors arriving at a civil war event on a Friday night are notorious for singing, drinking, or talking for hours on end. Friday nights are like family reunions. In most cases you hadn’t seen friends in months, so that first night is a time to socialize, get reacquainted, retell old war stories, sing, drink, and laugh.

After breakfast of bacon, hardtack, and coffee, it was time to form the battalion.

Officer’s call had been much earlier, so when Captain Tom came back it was to inform us we would be 4th company in line. We also discovered we were biggest company in the battalion, with approximately 35 men, so we would have the color guard with us. Several of the Tater Mess boys volunteered to act in this capacity and when it came time for us to take the field, they would be on our left.

Officer’s call had been much earlier, so when Captain Tom came back it was to inform us we would be 4th company in line. We also discovered we were biggest company in the battalion, with approximately 35 men, so we would have the color guard with us. Several of the Tater Mess boys volunteered to act in this capacity and when it came time for us to take the field, they would be on our left.During battalion formation we met our battalion commander, Lt. Col. Don Gross. I think he must have been a Marine Corp drill instructor in a previous life. He barked and snapped like a bulldog, but was quick to also heap praise when we did something right. Col. Gross carried no sword nor did he carry sidearm, sash, waist belt or other accouterments on his person. All he had on was his uniform and a Hardee hat.

During the first drill, he taught us forming divisions from a battalion front. “By the right of companies, to the rear into column, battalion right face.” This was reminiscent of drill I remember doing during the 125th anniversary reenactment at First Bull Run in June 1986. At events during the nineties and in this current century, I haven’t been involved in too many events where battalion drill is taught too much.

We marched in column of divisions, then wheeled into battalion line. From a battalion front, we also learned to move the right and left division to form behind the center division (two companies formed one division). A reversal of this same move was to place the center and the left division behind the right division. It basically amounted to learning how to walk and chew gum.

After about an hour of this entertainment, we were allowed a fifteen-minute break, then we formed up for bayonet drill. The whole battalion, some 200 men, was spaced about ten paces from one another and was instructed in the evolutions and convolutions of bayonet aerobics. Guard, parry, thrust, advance, repel, right and left volt, right and left rear volt, and the popular leap to the rear. We did such twists, turns, and gyrations that a ballerina would have been impressed. What this hobby needs is someone to create a workout video. How about-‘Leap to the Rear with Richard Simmons.’

After this aerobic workout was over, we had almost an hour before we had to get ready for the 1PM battle. Once given the command to dismiss, the boys scattered like the autumn leaves in a number of directions. Some went to gulp down lunch; I think Maki had beans and ham. Another distraction was to go visit sutler row. Fall Creek and Del Warren were the two big outfitters here. Two or three smaller outfits whose name is unimportant. One lady sold baked goods and liquid refreshment.

At the far end of sutler row was Robert Szabo, the master of the wetplate. There was another fellow next door who also did wet plate photography and I was told he had been an apprentice of Szabo who had finally struck out on his own. Both men had a lot of work come their way during the weekend. Reenactors decked out in their finest or grimiest outfits came to sit for a tin or ambro type from one of these gentlemen. I was told Robert Szabo is soon to return to Virginia, after several years in Missouri. Prairie Grove was his last event in the Trans-Mississippi. His MYSPACE website includes many outstanding portraits from the weekend at Prairie Grove, Arkansas.

No money to spend on sutler row for an image, baked good, or trinket from Fall Creek? Closer to the camps was a dogtrot cabin taken over by the US Sanitary Commission. Run by an older gentleman named Major Hershel Stroud and assisted by some mature ladies, the soldiers were offered a cornucopia of baked goods, fruits, hard boiled eggs, peanuts,

No money to spend on sutler row for an image, baked good, or trinket from Fall Creek? Closer to the camps was a dogtrot cabin taken over by the US Sanitary Commission. Run by an older gentleman named Major Hershel Stroud and assisted by some mature ladies, the soldiers were offered a cornucopia of baked goods, fruits, hard boiled eggs, peanuts,coffee, and lemonade free of charge. A lot of time, energy, and money must have been spent, and with very little fanfare, to just give food away. I don’t recall if there was a donation box or tip jar, but these hard working souls will surely get their reward in heaven. Apparently these fine people have been doing this impression for a number of years. I recall a 2002 Perryville event where these same Sanitary Commission people were present. At that time one of the ladies was dressed as a nun.

At about 12:30, we heard the bugle call for assembly. Every man Jack had to drop what ever they were doing, pick up musket and traps, and fall into their company formation. Once the company was assembled, roll taken, and men counted off, we marched up to our respective places in the battalion color line.

Some pushing and shoving was required with some dressing of the lines to ‘give way left’ and the line was formed to the satisfaction of the colonel. ‘Battalion right face,’ we formed our fours, then ‘forward march’ we went away from camp, and down the face of the hill for nearly a quarter-mile to a semi-flat land that was once a corn and wheat field. Further ahead about another quarter-mile to the northeast was the Illinois River; its width maybe fifty yards across from one end to the other. The field our battalion halted was the spot where the 20th Wisconsin and the 19th Iowa, two regiments from Herron’s Division, advanced across on that morning of December 7th.

The colonel gave the command, ‘on the right by files into line’, once we arrived at a midway point on this field. Each file, one after the other, executed a crisp right turn and halted. Soon the entire battalion was in a straight line of battle facing in a new direction. That new direction, which was just in front of us and some three hundred yards away, was the same slope that the 20th Wisconsin and the 19th Iowa had to climb when they were ordered to silence the Rebel artillery posted there.

In just about the same place as they’d been almost 150 years ago, we could see about ten Confederate guns pointed right at us. Fortunately, we had some fire power of our own in the form of a Union Battery about 30 paces in front of our battalion line. There was one Parrot or James gun, but the rest might have been Napoleon’s. At least six or eight men ran around each gun like men in a Chinese fire drill. I never saw so much red piping in my life on uniforms and hats. One team had matching red kepi’s.

We were told that the Rebs would begin the contest, so the Colonel gave us the command to ground arms and rest. We could lolly-gag about, shoot the breeze, catnap, take a smoke break, or eat out of the haversack as long as we didn’t wander off too far. I walked from one end of the battalion line to the other taking random photos of the men as well as the artillery crew as we waited for the opening kickoff.

We were told that the Rebs would begin the contest, so the Colonel gave us the command to ground arms and rest. We could lolly-gag about, shoot the breeze, catnap, take a smoke break, or eat out of the haversack as long as we didn’t wander off too far. I walked from one end of the battalion line to the other taking random photos of the men as well as the artillery crew as we waited for the opening kickoff.Finally after about a half-hour of waiting, the Rebel guns began belching at us. That was the cue for the Union artillery to spring into action. For the next several minutes (could have been fifteen minutes) the two artillery forces spewed smoke and thunder back at forth at each other. One gun (might have been the Parrot) must have used two pounds of black powder because every time it fired, the ground shook like it was the New Madrid earthquake.

During this heated exchange, us infantry boys were instructed to ‘hunker down’ or

‘take a knee.’ This was pure method acting as we were playing the part of Herron’s boys and we didn’t want the cannonball of the enemy to hit us, but instead we visualized the shells ‘passing harmlessly over our heads.’ At a reenactment, the hobbyist is required to do a lot of method acting. It is all part of the experience of play acting and even though no lead projectile is ever fired, if you get to close to the receiving end of a musket, a black powder flash to the face will hurt. If you get too close to a cannon going off, the concussion can kill.

‘take a knee.’ This was pure method acting as we were playing the part of Herron’s boys and we didn’t want the cannonball of the enemy to hit us, but instead we visualized the shells ‘passing harmlessly over our heads.’ At a reenactment, the hobbyist is required to do a lot of method acting. It is all part of the experience of play acting and even though no lead projectile is ever fired, if you get to close to the receiving end of a musket, a black powder flash to the face will hurt. If you get too close to a cannon going off, the concussion can kill.The artillery duel soon ended and the colonel ordered us to our feet. Our lines were dressed and our muskets were loaded. The bugle blasted out a tune and the entire battalion marched forward. The ground was a little uneven here and there, but we were able to keep somewhat of a straight line as we advanced. Every couple of paces we were reminded to ‘guide on the colors’ or ‘straighten up that alignment.’ It was another example of trying to walk and chew gum. To maintain a touch of elbow was the key in maintaining unit cohesion. If the men drifted and the lines broke, we would look more like a herd of cows than a well drilled fighting unit.

We had got our cue to advance once we saw that the rebel artillery had been silenced and its crews had skeddadled out of the picture. The avenue was clear for us to go up the hill and occupy the heights. Only a few foolhardy graybacks stood between us and the summit and these gents were brushed aside with a battalion volley.

The command was given to charge bayonet. No bayonets were fixed, but the men in the front rank had the muskets out in front in the guard position while the rear rank men went to right shoulder shift. No other command was given but within a second, unit cohesion had evaporated and the men were scampering up that hill like an angry mob storming Castle Frankenstein. Even though passion had over taken each man, one had to be wary of roots or small rocks that might turn an ankle. Mixed in with Indian war cries and bellows of rage were words of caution to ‘watch your footing.’

At the top of the hill sat the Archibald Borden House. The Borden House had burned down the day after the original battle but has been rebuilt and it sits to this day. Behind the Borden House was an apple orchard. That too has been restored.

The two–story Borden House loomed right before us, once we reached the top of the hill. Shouted commands by the officers and the battalion was instructed to reform on the other side of the house. The right wing went one way and the left wing went another. On the back end of the house the battalion was instructed to take a knee behind the snake fence and commence firing. The snake fence was only knee high, so we had to flatten on our bellies to shoot then reload by rolling on our backs. Two hundred yards away and emerging from the shrubbery that was the old apple orchard, came the entire Confederate infantry.

The men of the 20th Wisconsin and the 19th Iowa had scaled the slope and overran the Confederate battery, then as they advanced on either side of the Borden House, they saw they’d run into a trap. Coming through the orchard just ahead was a Rebel infantry brigade under James S. Fagan and dismounted cavalry under Jo Shelby supported by Bledsoe’s Battery.

We threw blistering volleys into the advancing graybacks but there was no stopping that tidal wave of doom. Slowly and painfully, men began to fall back. My musket had fouled a couple times, so I stepped back to pick the crud out of the cone. Back on the line, I was able to clear my piece, but I must have put two cartridges down the barrel. It went off like a twelve-pounder and my pards almost wet themselves.

Onward that crushing gray wall came. The boys in blue were being whittled away and it was time to vamoose. We picked ourselves away from the fence and scurried back around to the other side of the Borden House. A couple more pot shots were hurled in a feeble attempt at the foe, but it was no use. About face and fallback was the order given.

One touching scene I witnessed was this. A Union soldier had collapsed against the front porch. He’d been ‘wounded’ or something and could go no further. A little boy about three or four stood over him with a look of distress. The boy was decked out in a Union uniform and clutched a hospital flag. One look told me they were father and son. The Rebs were approaching and the father was telling his son to go on and leave him. Reluctantly, the little boy left his father’s side and rejoined our gradually shrinking battalion. As we retreated down that hill, the little boy continued to ask about his daddy.

“Will the Rebs hurt my daddy?”

Being so little, he thought his dad was really in danger and maybe didn’t realize it was all part of the play-acting. I attempted to stay in first person and explain to him that “the Rebs won’t hurt your daddy” or “your daddy wouldn’t want you to be captured by the Rebs.” Another soldier, a friend of the father, called the boy by name and took him under his wing till the battle ended.

Eventually the battle ended. The Frontier battalion had suffered 75% casualties. Holmes Brigade had started out with 35 men, now we were down to 8. Gathering what men we had left, the battalion staggered back to camp. We were all fagged out after this ordeal. You could have knocked me over with a feather. After the battle was concluded and the applause had died down, resurrection was declared and all the boys ‘rose up from the dead’ and returned to camp. Darkness was a short hour or two away, but before the Colonel would allow his men to rest, he instructed us to clean our weapons. There would be an inspection on Sunday and woe betide the man with the dirty musket.

Maki had some old hot coffee on the fire. It had sat for hours and was undrinkable, but good enough to pour down the barrel. I couldn’t tell what was black powder and what was coffee coming out of the barrel, but at least something was coming out. I ran the rammer down the barrel, heard a satisfying ‘ting,’ and waited for supper.

Once the sun fell, the fires were built up, songs were started, and liquor came out.

Once the sun fell, the fires were built up, songs were started, and liquor came out.

Holmes Brigade is notorious for its end of season toast. We tip a mucket of some concoction and reflect on the passing year. This year we had three gallons of hard cider.

About 8PM, a few of us decided to wander over to Miss Tula’s. About one hundred yards south of the Union Camp, near the dog trot cabin housing the US Sanitary Commission people, was a single large sutler type tent. Inside the tent were three wooden tables with about eight chairs apiece and in the corner was a small makeshift bar. On the wall behind the bar was an oil painting of a nude woman with lettering that read ‘Miss Tula’s Tavern’. Candle lanterns hung from every upright pole supporting the walls of the tent, there were candles on each table, and suspended from the ceiling was a wagon wheel with four or six more candle lanterns suspended from the spokes. This candle lighting created quite an effective and somber mood.

Inside Miss Tula’s, men were drinking beer or shots of rye whiskey, telling stories, singing Irish ballads or patriotic songs, telling dirty limericks, playing checkers, smoking, and/or flirting with one of Miss Tula’s ‘soiled doves’. Miss Tula, wearing a raspberry red zouave outfit and matching fez, wandered among the patrons, shared a laugh, a drink, or playfully slapped at the hand of someone who pinched her bottom. Miss Tula had been at the Stand of Colors event but I’d missed visiting it because I was either too tired or too busy pulling ticks off myself.

The way I understand it, no alcohol could be sold on park property, but it could be given away. In lieu of actually handing over cash money for a drink, Miss Tula gladly accepted a donation. One guy 'donated' $20 and 'purchased' several rounds for the guys.

Miss Tula had a barkeep who stood being the bar and worked the tap. Occasionally, he'd put more ginger snap cookies on the table or replace a candle after it had gone out. Midway through the evening, one of our young lieutenants brought his own bottle of rye whiskey, but the bartender did not fuss. The only time the bartender raised his voice was when a Reb walked through the entrance.

entrance.

“No Johnny Rebs served here!” was the cry as the grayback was shown the door.

I don't know if this rule changed from event to event, but this weekend, Miss Tula would not allow any Confederates into the tavern. On the center of the bar was a portrait of Abe Lincoln. In a tavern surrounded by paintings of nudes, a portrait of the president seemed a bit out of place.

The tavern could only hold about 30 men, but a few others came and went, then about 10PM there was a minstrel show. Members of the Tater Mess rubbed burnt cork on their faces and did a song, dance, and comedy routine. During that 30-minute session, the tavern swelled to standing room only as more boys came in to see Zip Coon, Cuffy, Stepin Fetchit, and ManTan shuck and jive. (No pics available except upon request)

On Sunday morning we had another battalion drill, but this time we didn't have to carry our muskets. Huh? I never drilled without a musket before, but it was so decreed by Col. Gross.

I think I’ve rambled on long enough with this tale. This would be a prime example of chin music-that is talking too much to the point of babbling. I certainly don’t know how to tell a short story.

Be that as it may, the short and sweet version of the battle on Sunday was this: on Sunday, December 7, 2008, the anniversary of the original 1862 battle, the US Frontier battalion-those of us who were left-portrayed General Blunts Division.

General Blunt was nearly eight miles of Prairie Grove at Cane Hill, but upon hearing the sounds of the guns, he put his men on the road. The battle had begun at about 10AM when Herron first arrived on the scene. Blunt and his men arrived at Prairie Grove at approximately 3PM and deployed into line of battle.

In 1862, the battle seesawed back and forth until darkness fell. Out of ammunition and 30 miles from his supply line, Hindman and his Confederates abandoned the field. In 2008, the battle reenactment was halted not once, not twice, but three times due to real life injuries.

With the lines barely one hundred yards apart, play was halted because a Rebel Cavalryman fell off his horse. The man tried to get up under his own power and walk away, but his knee gave out and he collapsed. The guy also had the ugliest length of shoulder black hair. For a minute it looked like he had on a Halloween fright wig. Play was resumed once the guy was hauled away but less than ten minutes later play was halted again. This time the injury was a bit more serious. A Rebel color bearer had fallen backwards in the pretext of taking a hit. As he fell back, the pointy end of the flagpole jabbed another Rebel reenactor in the neck.

There are all kinds of professional people in this hobby, teachers, lawyers, students, and businessmen. It just so happens that the hobby also has a fair share of folks who are in the medical profession, including real life doctors, nurses, and EMT’s.

Once the emergency was known two or three guys from the Federal lines leaped across no-man’s land to join two or three Johnny Rebs to deal with the real life emergency.

In a battle reenactment, safety is Job one. North and South play-acting is put aside and modern medical skills come into play. In the past, I’ve seen a lot of injuries suffered on the reenactment field. Some take the form of simple ankle sprains or someone falls off a horse or a knee goes out or someone gets stabbed with a bayonet or falls face first on the barrel of his musket. No matter how much you try to maintain first person and put yourself in the heat of the moment, you must also be aware that accidents can happen.

So play was halted for about another fifteen minutes till the fellow could be patched up and carted off the field. Fortunately the cut on the neck was nowhere near an artery. During this down time, both Union and Confederate infantry lines hurled playful insults at one another.

When play was finally resumed, the Federal battalion fired some volleys and advanced. Though our line was not as big as the Confederates were, the object this day was we would win. So we pushed and pushed the graybacks all the way back to the base of Borden House hill. It was then that play was again halted because of another injury on the Rebel side. I’m not sure what happened, but someone later said they thought a 16-year old had had a heart palpitation.

We had been on the field about an hour, including the injury time-outs. It was unanimously decided that the game was over. Colonel Gross marched us away from the battlefield and back to our camps we went. I’m sure the spectators didn’t get their moneys worth this day, but no one can predict injuries. It was close to 3PM. Now came the unpleasant task of packing up for the long drive back home. It took Maki and I about a half-hour to load his truck and changed back into our modern clothes.

And so ends this short story on the Dec 6-7, 2008 battle reenactment of Prairie Grove, Arkansas. I want to thank you for reading this and wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

We had got our cue to advance once we saw that the rebel artillery had been silenced and its crews had skeddadled out of the picture. The avenue was clear for us to go up the hill and occupy the heights. Only a few foolhardy graybacks stood between us and the summit and these gents were brushed aside with a battalion volley.

The command was given to charge bayonet. No bayonets were fixed, but the men in the front rank had the muskets out in front in the guard position while the rear rank men went to right shoulder shift. No other command was given but within a second, unit cohesion had evaporated and the men were scampering up that hill like an angry mob storming Castle Frankenstein. Even though passion had over taken each man, one had to be wary of roots or small rocks that might turn an ankle. Mixed in with Indian war cries and bellows of rage were words of caution to ‘watch your footing.’

At the top of the hill sat the Archibald Borden House. The Borden House had burned down the day after the original battle but has been rebuilt and it sits to this day. Behind the Borden House was an apple orchard. That too has been restored.

The two–story Borden House loomed right before us, once we reached the top of the hill. Shouted commands by the officers and the battalion was instructed to reform on the other side of the house. The right wing went one way and the left wing went another. On the back end of the house the battalion was instructed to take a knee behind the snake fence and commence firing. The snake fence was only knee high, so we had to flatten on our bellies to shoot then reload by rolling on our backs. Two hundred yards away and emerging from the shrubbery that was the old apple orchard, came the entire Confederate infantry.

The men of the 20th Wisconsin and the 19th Iowa had scaled the slope and overran the Confederate battery, then as they advanced on either side of the Borden House, they saw they’d run into a trap. Coming through the orchard just ahead was a Rebel infantry brigade under James S. Fagan and dismounted cavalry under Jo Shelby supported by Bledsoe’s Battery.

We threw blistering volleys into the advancing graybacks but there was no stopping that tidal wave of doom. Slowly and painfully, men began to fall back. My musket had fouled a couple times, so I stepped back to pick the crud out of the cone. Back on the line, I was able to clear my piece, but I must have put two cartridges down the barrel. It went off like a twelve-pounder and my pards almost wet themselves.

Onward that crushing gray wall came. The boys in blue were being whittled away and it was time to vamoose. We picked ourselves away from the fence and scurried back around to the other side of the Borden House. A couple more pot shots were hurled in a feeble attempt at the foe, but it was no use. About face and fallback was the order given.

One touching scene I witnessed was this. A Union soldier had collapsed against the front porch. He’d been ‘wounded’ or something and could go no further. A little boy about three or four stood over him with a look of distress. The boy was decked out in a Union uniform and clutched a hospital flag. One look told me they were father and son. The Rebs were approaching and the father was telling his son to go on and leave him. Reluctantly, the little boy left his father’s side and rejoined our gradually shrinking battalion. As we retreated down that hill, the little boy continued to ask about his daddy.

“Will the Rebs hurt my daddy?”

Being so little, he thought his dad was really in danger and maybe didn’t realize it was all part of the play-acting. I attempted to stay in first person and explain to him that “the Rebs won’t hurt your daddy” or “your daddy wouldn’t want you to be captured by the Rebs.” Another soldier, a friend of the father, called the boy by name and took him under his wing till the battle ended.

Eventually the battle ended. The Frontier battalion had suffered 75% casualties. Holmes Brigade had started out with 35 men, now we were down to 8. Gathering what men we had left, the battalion staggered back to camp. We were all fagged out after this ordeal. You could have knocked me over with a feather. After the battle was concluded and the applause had died down, resurrection was declared and all the boys ‘rose up from the dead’ and returned to camp. Darkness was a short hour or two away, but before the Colonel would allow his men to rest, he instructed us to clean our weapons. There would be an inspection on Sunday and woe betide the man with the dirty musket.

Maki had some old hot coffee on the fire. It had sat for hours and was undrinkable, but good enough to pour down the barrel. I couldn’t tell what was black powder and what was coffee coming out of the barrel, but at least something was coming out. I ran the rammer down the barrel, heard a satisfying ‘ting,’ and waited for supper.

Once the sun fell, the fires were built up, songs were started, and liquor came out.

Once the sun fell, the fires were built up, songs were started, and liquor came out.Holmes Brigade is notorious for its end of season toast. We tip a mucket of some concoction and reflect on the passing year. This year we had three gallons of hard cider.

About 8PM, a few of us decided to wander over to Miss Tula’s. About one hundred yards south of the Union Camp, near the dog trot cabin housing the US Sanitary Commission people, was a single large sutler type tent. Inside the tent were three wooden tables with about eight chairs apiece and in the corner was a small makeshift bar. On the wall behind the bar was an oil painting of a nude woman with lettering that read ‘Miss Tula’s Tavern’. Candle lanterns hung from every upright pole supporting the walls of the tent, there were candles on each table, and suspended from the ceiling was a wagon wheel with four or six more candle lanterns suspended from the spokes. This candle lighting created quite an effective and somber mood.

Inside Miss Tula’s, men were drinking beer or shots of rye whiskey, telling stories, singing Irish ballads or patriotic songs, telling dirty limericks, playing checkers, smoking, and/or flirting with one of Miss Tula’s ‘soiled doves’. Miss Tula, wearing a raspberry red zouave outfit and matching fez, wandered among the patrons, shared a laugh, a drink, or playfully slapped at the hand of someone who pinched her bottom. Miss Tula had been at the Stand of Colors event but I’d missed visiting it because I was either too tired or too busy pulling ticks off myself.

The way I understand it, no alcohol could be sold on park property, but it could be given away. In lieu of actually handing over cash money for a drink, Miss Tula gladly accepted a donation. One guy 'donated' $20 and 'purchased' several rounds for the guys.

Miss Tula had a barkeep who stood being the bar and worked the tap. Occasionally, he'd put more ginger snap cookies on the table or replace a candle after it had gone out. Midway through the evening, one of our young lieutenants brought his own bottle of rye whiskey, but the bartender did not fuss. The only time the bartender raised his voice was when a Reb walked through the

entrance.

entrance.“No Johnny Rebs served here!” was the cry as the grayback was shown the door.

I don't know if this rule changed from event to event, but this weekend, Miss Tula would not allow any Confederates into the tavern. On the center of the bar was a portrait of Abe Lincoln. In a tavern surrounded by paintings of nudes, a portrait of the president seemed a bit out of place.

The tavern could only hold about 30 men, but a few others came and went, then about 10PM there was a minstrel show. Members of the Tater Mess rubbed burnt cork on their faces and did a song, dance, and comedy routine. During that 30-minute session, the tavern swelled to standing room only as more boys came in to see Zip Coon, Cuffy, Stepin Fetchit, and ManTan shuck and jive. (No pics available except upon request)

On Sunday morning we had another battalion drill, but this time we didn't have to carry our muskets. Huh? I never drilled without a musket before, but it was so decreed by Col. Gross.

I think I’ve rambled on long enough with this tale. This would be a prime example of chin music-that is talking too much to the point of babbling. I certainly don’t know how to tell a short story.

Be that as it may, the short and sweet version of the battle on Sunday was this: on Sunday, December 7, 2008, the anniversary of the original 1862 battle, the US Frontier battalion-those of us who were left-portrayed General Blunts Division.

General Blunt was nearly eight miles of Prairie Grove at Cane Hill, but upon hearing the sounds of the guns, he put his men on the road. The battle had begun at about 10AM when Herron first arrived on the scene. Blunt and his men arrived at Prairie Grove at approximately 3PM and deployed into line of battle.

In 1862, the battle seesawed back and forth until darkness fell. Out of ammunition and 30 miles from his supply line, Hindman and his Confederates abandoned the field. In 2008, the battle reenactment was halted not once, not twice, but three times due to real life injuries.

With the lines barely one hundred yards apart, play was halted because a Rebel Cavalryman fell off his horse. The man tried to get up under his own power and walk away, but his knee gave out and he collapsed. The guy also had the ugliest length of shoulder black hair. For a minute it looked like he had on a Halloween fright wig. Play was resumed once the guy was hauled away but less than ten minutes later play was halted again. This time the injury was a bit more serious. A Rebel color bearer had fallen backwards in the pretext of taking a hit. As he fell back, the pointy end of the flagpole jabbed another Rebel reenactor in the neck.

There are all kinds of professional people in this hobby, teachers, lawyers, students, and businessmen. It just so happens that the hobby also has a fair share of folks who are in the medical profession, including real life doctors, nurses, and EMT’s.

Once the emergency was known two or three guys from the Federal lines leaped across no-man’s land to join two or three Johnny Rebs to deal with the real life emergency.

In a battle reenactment, safety is Job one. North and South play-acting is put aside and modern medical skills come into play. In the past, I’ve seen a lot of injuries suffered on the reenactment field. Some take the form of simple ankle sprains or someone falls off a horse or a knee goes out or someone gets stabbed with a bayonet or falls face first on the barrel of his musket. No matter how much you try to maintain first person and put yourself in the heat of the moment, you must also be aware that accidents can happen.

So play was halted for about another fifteen minutes till the fellow could be patched up and carted off the field. Fortunately the cut on the neck was nowhere near an artery. During this down time, both Union and Confederate infantry lines hurled playful insults at one another.

When play was finally resumed, the Federal battalion fired some volleys and advanced. Though our line was not as big as the Confederates were, the object this day was we would win. So we pushed and pushed the graybacks all the way back to the base of Borden House hill. It was then that play was again halted because of another injury on the Rebel side. I’m not sure what happened, but someone later said they thought a 16-year old had had a heart palpitation.

We had been on the field about an hour, including the injury time-outs. It was unanimously decided that the game was over. Colonel Gross marched us away from the battlefield and back to our camps we went. I’m sure the spectators didn’t get their moneys worth this day, but no one can predict injuries. It was close to 3PM. Now came the unpleasant task of packing up for the long drive back home. It took Maki and I about a half-hour to load his truck and changed back into our modern clothes.

And so ends this short story on the Dec 6-7, 2008 battle reenactment of Prairie Grove, Arkansas. I want to thank you for reading this and wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.