featuring John Henry, the rag doll who can talk

CHAPTER 1

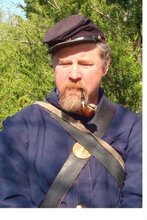

It seemed like many miles and many days had passed since the chase began. The 3000 blue-clad soldiers of Colonel Samuel Holmes' brigade had followed the enemy clear across one state and into another. These Union volunteers were long legged boys who had been raised on farms in Iowa and Illinios and used to outdoor living and hardship. Holmes fondly called them his greyhounds. But the Rebs were farmboys also; a mixture of Missourians and Arkansans. They were as difficult to slow down and catch as wild hares. Holmes sent about a hundred of his 'greyhounds' forward as skirmishers, to try to make contact with the enemy and perhaps make them turn and fight, but these boys were always driven away.

Many miles ahead was the raw and ragged wall of a rocky plateau, the foothills to a range of forbidding mountains. We’ve trapped them, Colonel Holmes thought, or at least slowed them down long enough for us to attack. Once cornered into these mountains he hoped the Rebs would finally turn and fight. But his celebration was short lived, because overhead, the clouds began to thicken and rumble. Within minutes, a heavy rain came down, slowing the pace of Holmes Brigade to a crawl. Under the cover of rain, the Rebs scaled the plateau and easily slipped away.

By the time the Union Army arrived many hours later, the plateau, towering before them, was thick with heavy black mud. No way could man or beast scale those slippery heights. At the base of the plateau, and unseen from a distance because of trees, was a wide river. The heavy rains had turned the waters into a raging deathtrap for anyone trying to ford it.

A loyal citizen, who was familiar with the area, told Colonel Holmes that the country beyond the plateau was a poor source for forage and shelter. At some point, he concluded, the enemy would have to return across the river to greener pastures or die in the mountains.

“We will wait for them to return”, Holmes smugly declared, “and give them a welcome back reception they’ll never forget”.

And so Holmes Brigade settled down to wait. But rather than lolly-gag about idly, Holmes put his men to work building earthworks all along the banks of the swiftly flowing river. In these works were placed large bore artillery guns. To the rear of these earthworks was a small tree-lined valley separated in two halves by a country road. Astride this road was the rest of Holmes’ Brigade in reserve: supply wagons, extra artillery, horse soldiers, and small tent city housing officers and men. An old two-room cabin sat in this valley, but the family had long since been driven away by the war.

Once the earthworks were complete, Holmes Brigade continued to wait and wait. Then one morning, the storm clouds separated and the sun poked out its shiny face. A spy went up in a hot air balloon and looked the area over with the aid of a telescope but when he came down, it was with bad news.

“ I can’t find hide nor hair of the enemy,” the spy unhappily announced, “The mountains have swallowed them up or else they’d found another avenue of escape and gone around our flank.”

“No, by thunder,” Holmes screeched, pulling at his hair and beard in frustration, “they’ll cross here, at this spot. I know it in my bones.”

Samuel Holmes was using the old farmhouse as his headquarters and he was having a conference with his staff, including his chief of cavalry. No one could agree on a course of action.

“Sir, a patrol of horse soldiers was sent out yesterday across the river and beyond the plateau,” the old cavalry chief said, “but the rains washed any trace of the enemy and it appears as if they’ve simply vanished.”

“This could have been the best campaign of my career,” Holmes croaked, “ I could have gotten my general’s star at last, but you ruined it,” he spat, “I’m surrounded by dunderheads. You boot lickers can’t find the stinking Rebs and all you can advice me to do is withdraw.”

“Sir, the telegram came from Sam Grant two days ago,” said an aide, “he needs our Brigade for his campaign against Vicksburg. We’ve been camped here for almost a month, “ the aide offered, “but still no sign of the enemy. It’s obvious they’ve given us the slip.”

“Slip, hell, “Holmes screamed in frustration. Enraged, he picked up his chamber pot and heaved clear across the room where it shattered and splashed its vile contents all down the wall.

“You old grannies let the Rebs slip through you’re fingers and denied me my star,” he hooted. His face was purple with rage and he pounded his fists into the wooden table till splinters flew.

“I could have been a general and this one campaign could have given me a proper command, instead of that old drunken fool, Sam Grant.”

The officers of Samuel Holmes’ staff knew it was pointless to argue with the man. His resentment against Grant was notorious ever since that day many years ago in Galena, Illinois when an empty liquor bottle thrown by Sam Grant accidentally hit him in the head.

Holmes had hoped to bag the vile damn Rebs before now and it appeared that chance had slipped away for good and that would mean a black mark on his record and possibly a loss in command. Suddenly there was an interruption as a skinny enlisted man in a white apron walked into the cabin. This was Donnyboy, Colonel Holmes’ personal cook, valet, and housekeeper.

“ Beg pardon, sir, but the river has quieted down enough that the catfish are out and hungry.”

Samuel Holmes swept the skinny youth in his arms.

"Oh, Donnyboy, you restored my soul."

He turned to face his staff. He had the glowing look of a boy about to skip school.

“Men, I’ll be back in a few hours. At that time we’ll discuss plans for withdrawing the Brigade and rejoining II Corp. In the meantime, send all the extra equipment some 10 miles to the rear. Also, get MacEye to finish boxing up that contraband so it can get sent to St. Louis. We’ll move the army at nightfall, tonight.”

Holmes leaped out of the cabin into the morning sunshine and danced and sang all the way to the riverbank. He passed groups of soldiers along the way who waved or called him by name. Even the birds came out of hiding and sensing this light hearted spirit, filled the air with song. With some sense of normalcy at last, the men sat down to eat their breakfast of sowbelly, hardtack, and coffee.

Once their commander had departed, the staff officers all breathed a sigh of relief. Now it was their task to prepare the army to march. The biggest challenge was dealing with the stuff in the barn.

The old barn was a short distance from the farmhouse and had been declared off limits to the soldiers. Even though the roof was sound and weatherproof, it was well guarded against trespassers for inside was contraband liberated by Union cavalrymen on a recent raid. The booty consisted of such things as tea sets, dinnerware, cutlery, cut glass brandy decanters, fancy candelabras, several ivory-handled combs and hairbrushes, fancy oil paintings, two chamber pots, and one brass tub big enough for to bathe a grown man.

If given a few more days, Lieutenant John MacEye could have done it, but no way could he box up all that crap before nightfall. MacEye was currently a supply officer, but had been a carpenter before the war therefore Samuel Holmes had volunteered him for this most crucial duty. But damn me if I can find proper lumber to build the boxes for this blamed contraband and stuff, MacEye silently fumed.

After hours of cursing to himself and pulling at his hair, he turned and shouted for the Sergeant Major. From the hayloft above him came a scraping of feet. A shower of loose hay fell the ground, followed by a pair of fat legs attached to a very large man. As he brushed the hay off himself, MacEye warily eyed the grinning ogre in the blue suit.

MacEye was a small round man of Nordic heritage. Both legs had been broken after a tragic tumble from a barstool and had refused to heal properly. Just under three feet tall, MacEye has to lean backwards to look up at the giant before him.

Sergeant Major Randy Rogers was a freak of nature, having been wounded many times and bearing the scars to prove it. But no wound was ever mortal, because Randy was encased in a layer of fat. He was a man as wide as he was tall with a heavy black beard matted with bits of old food. He must have been napping because when he yawned, he made a noise like a foghorn.

“Randy,” MacEye spoke softly and slowly so the giant would understand, “we need to get these valuables boxed up and shipped by this evening. However, I'm running out of proper wood and stuff. Please assign some men to forage for some building materials."

"Yes, loo tenant! I think I know just the men,” said Rogers as he put his paw to his cap in salute.

Some yards away, a group of blue coated men were huddled around a campfire. The flames didn’t put out much heat, so the men sipped from tin cups and prayed that the hot coffee would thaw out their bones. What had the men spellbound for the moment was not the hope of warmth, but the promise of a hot breakfast. In a long handled skillet, hunks of sowbelly were being fried. The owner of the skillet was bent over at the waist and used a fork to flip and turn the meat in its sizzling grease. Each man had been promised some of the fatback, so they were content to stand back with glazed eyes and wait. The drool that was running down their mouths made them look like rabid dogs.

Suddenly the arrival of the huge ape-like creature wakens the soldiers from of their trance. Sergeant Major Rogers had legs as thick as tree trunks and he stomped over to the campfire with the stride of a bull elephant. The soldiers felt the earth tremble. Rogers stopped before the blaze, unmindful of the smoke that whirled around his head, and swept his red piggish eyes back and forth.

With a wide grin, the soldier with the skillet unfolded himself and rose to his full height.

"Good mornin' Randy," exclaimed Higgy, a man who was as tall and thin as a washboard. Higgy had beady eyes set in a pinched face and a black handlebar mustache hanging under a long Roman nose. His uniform trousers and jacket were nearly worn out. Both had been patched a number of times, plus carried a variety of unidentifiable stains. The forage cap, atop a shock of black hair, might have been used to carry everything from garden vegetables to a bowel movement. E PLURIBUS UNUM was scrawled in the upturned brim of the cap. Overall, Higgy looked like the scarecrow that had just stepped out of a cornfield.

From a mouth a black as a cavern and with breath just a foul, the Sergeant Major spoke.

"Lt. MacEye is looking for some volunteers for a wood foraging detail and you're it," he declared, “I want you to take the Bagg's about three miles west to the village there, and bring back as much lumber as you can find. Hitch a mule to one of those wagon's from over yonder." He pointed toward the fence line where several were parked.

" I think there's some privy's you can knock down that should provide usable lumber."

“But, Randy. Why do we need to go into the village fer firewood? There’s plenty fine woods right here. Besides, I heard a feller say he heard wagon wheels and such moving during the evening. He says the sesech might try to circle us and get us from behind."

“The wood is for Lieutenant MacEye’s box building project,” the Sergeant Major growled, “Sam Holmes wants him to crate up all the contraband that was ‘liberated’ from on the last raid. As far as worrying about funny noises, that’s none of your affair. That’s for the officers to worry about. "

Rogers turned as if to walk away, but instead he spun around, snatched the skillet out of Higgy’s hand, and tipped the entire contents down his throat, hot grease and all.

“Now get those Bagg’s and get over to the village,” he barked, spewing grease all down his beard.

With a shrug of resignation and a sorrowful look back at his hungry comrades, Higgy walked about fifty paces to three gray, man shaped bundles. The men under these wool blankets were so tightly wrapped against the cold, only their snores escaped. Going from one to the other, he used the flat of his skillet on their backsides.

“Reach for the sky!”

Struggling out of their blankets were the brothers Charlie, Butthead, and Erik Bagg. The brother's were wearing the same blue uniform as the Union Army, but of a description similar to Higgy’s. Instead of a military cap, the brothers were each wearing a low crowned black hat with a very narrow brim. In the army, this type of hat was called a "pork pie."

Charlie was tall with a long, angular face, a high forehead and sad hound dog eyes. He ran bony fingers through hair the color of wheat. Butthead was of stockier material, thick limbed with a round Irish face. A quick smile and laughing angel eyes made him a favorite with the ladies. Erik, on the other hand, had a quick temper to match his fiery red hair and goatee. He was doing most of the cursing as Higgy explained the wood detail.

As the Bagg's shuffled over to where the wagons were parked, Higgy stepped over to where a gum blanket hung over four stacked muskets. Removing the rubberized canvas, which had kept the weather off the weapons during the night, Higgy examined the assortment of leather belts and straps that were slung over the bayonets of each musket. Cartridge boxes with slings, waist belts, wool covered canteens, and of course, tarred canvas haversacks. These were the soldiers 'traps', so called because once the soldier had these items on his body, he felt trapped in them.

Higgy took one of the haversacks and peered inside.

John Henry, you awake down there little one?"

Peeping up from within the tarred haversack was a little black rag doll made from lint and the scraps of old rags. Black strands of yarn on its head were long as the tentacles on an octopus. The doll wore a red flannel shirt, bib overalls, and no shoes. The rag doll blinked once or twice, rubbed sleep out of mother-of-pearl button eyes and in a tiny voice exclaimed.

“No mo’ rain, Higgy? I’se gets a bit chill’d las’ night.”

“Don’t fret, John Henry,” Higgy said in his calmest voice,“Looks like the cold weather is behind us. Being the naturalist I am, I ‘spect today will be hot.”

In a couple minutes the Bagg brothers came back, leading a swayback mule hitched to a wagon.

“Say Higgy, look what the cat coughed up,” announced one of the Bagg’s.

Lying in the bed of the wagon was a soldier curled up and fast asleep.

“Well feed me corn and watch me crow!” the doll John Henry exclaimed.

While Higgy and the Bagg's might have looked like an unmade bed, this unconscious newcomer was a P.T.Barnum curiosity. He wore the same blue uniform as the rest of the Union Army. Instead of the fatigue or sack coat, he had on a long tailed military frock coat - the sleeves of which were rolled to the elbow exposing a very loud red checked shirt. Plus, the coat was unbuttoned, revealing a green satin vest with glass buttons. An equally gaudy purple kerchief was knotted in a bow at his throat. A slightly dented Hardee Hat lay at his side. It was fully decorated with the brim turned up on one side and fastened by a pin holding a spectacular ostrich plume.

The soldier had nearly feminine features including a button nose, full red lips, and delicate cheekbones. The exception to near perfect features was the single black eyebrow that stretched across his forehead like a fat hairy caterpillar.

“Why its Dave Sullivan, the grossest boy in the Union Army,” Higgy said.

"Look's like he got himself some ‘popskull’," answered Charlie as he held up an empty champagne bottle, "Phoowee! Smells like he took a bath in the stuff."

"We can't let the Sergeant Major find him like this," said Higgy, "we'll just have to take him along with us and try to get him cleaned up."

The rifles and traps were laid in the back of the wagon and with a flick of the reins, the mule was urged westward carrying Higgy, the Bagg's, an unconscious Dave Sullivan, and the little rag doll John Henry.

It seemed like many miles and many days had passed since the chase began. The 3000 blue-clad soldiers of Colonel Samuel Holmes' brigade had followed the enemy clear across one state and into another. These Union volunteers were long legged boys who had been raised on farms in Iowa and Illinios and used to outdoor living and hardship. Holmes fondly called them his greyhounds. But the Rebs were farmboys also; a mixture of Missourians and Arkansans. They were as difficult to slow down and catch as wild hares. Holmes sent about a hundred of his 'greyhounds' forward as skirmishers, to try to make contact with the enemy and perhaps make them turn and fight, but these boys were always driven away.

Many miles ahead was the raw and ragged wall of a rocky plateau, the foothills to a range of forbidding mountains. We’ve trapped them, Colonel Holmes thought, or at least slowed them down long enough for us to attack. Once cornered into these mountains he hoped the Rebs would finally turn and fight. But his celebration was short lived, because overhead, the clouds began to thicken and rumble. Within minutes, a heavy rain came down, slowing the pace of Holmes Brigade to a crawl. Under the cover of rain, the Rebs scaled the plateau and easily slipped away.

By the time the Union Army arrived many hours later, the plateau, towering before them, was thick with heavy black mud. No way could man or beast scale those slippery heights. At the base of the plateau, and unseen from a distance because of trees, was a wide river. The heavy rains had turned the waters into a raging deathtrap for anyone trying to ford it.

A loyal citizen, who was familiar with the area, told Colonel Holmes that the country beyond the plateau was a poor source for forage and shelter. At some point, he concluded, the enemy would have to return across the river to greener pastures or die in the mountains.

“We will wait for them to return”, Holmes smugly declared, “and give them a welcome back reception they’ll never forget”.

And so Holmes Brigade settled down to wait. But rather than lolly-gag about idly, Holmes put his men to work building earthworks all along the banks of the swiftly flowing river. In these works were placed large bore artillery guns. To the rear of these earthworks was a small tree-lined valley separated in two halves by a country road. Astride this road was the rest of Holmes’ Brigade in reserve: supply wagons, extra artillery, horse soldiers, and small tent city housing officers and men. An old two-room cabin sat in this valley, but the family had long since been driven away by the war.

Once the earthworks were complete, Holmes Brigade continued to wait and wait. Then one morning, the storm clouds separated and the sun poked out its shiny face. A spy went up in a hot air balloon and looked the area over with the aid of a telescope but when he came down, it was with bad news.

“ I can’t find hide nor hair of the enemy,” the spy unhappily announced, “The mountains have swallowed them up or else they’d found another avenue of escape and gone around our flank.”

“No, by thunder,” Holmes screeched, pulling at his hair and beard in frustration, “they’ll cross here, at this spot. I know it in my bones.”

Samuel Holmes was using the old farmhouse as his headquarters and he was having a conference with his staff, including his chief of cavalry. No one could agree on a course of action.

“Sir, a patrol of horse soldiers was sent out yesterday across the river and beyond the plateau,” the old cavalry chief said, “but the rains washed any trace of the enemy and it appears as if they’ve simply vanished.”

“This could have been the best campaign of my career,” Holmes croaked, “ I could have gotten my general’s star at last, but you ruined it,” he spat, “I’m surrounded by dunderheads. You boot lickers can’t find the stinking Rebs and all you can advice me to do is withdraw.”

“Sir, the telegram came from Sam Grant two days ago,” said an aide, “he needs our Brigade for his campaign against Vicksburg. We’ve been camped here for almost a month, “ the aide offered, “but still no sign of the enemy. It’s obvious they’ve given us the slip.”

“Slip, hell, “Holmes screamed in frustration. Enraged, he picked up his chamber pot and heaved clear across the room where it shattered and splashed its vile contents all down the wall.

“You old grannies let the Rebs slip through you’re fingers and denied me my star,” he hooted. His face was purple with rage and he pounded his fists into the wooden table till splinters flew.

“I could have been a general and this one campaign could have given me a proper command, instead of that old drunken fool, Sam Grant.”

The officers of Samuel Holmes’ staff knew it was pointless to argue with the man. His resentment against Grant was notorious ever since that day many years ago in Galena, Illinois when an empty liquor bottle thrown by Sam Grant accidentally hit him in the head.

Holmes had hoped to bag the vile damn Rebs before now and it appeared that chance had slipped away for good and that would mean a black mark on his record and possibly a loss in command. Suddenly there was an interruption as a skinny enlisted man in a white apron walked into the cabin. This was Donnyboy, Colonel Holmes’ personal cook, valet, and housekeeper.

“ Beg pardon, sir, but the river has quieted down enough that the catfish are out and hungry.”

Samuel Holmes swept the skinny youth in his arms.

"Oh, Donnyboy, you restored my soul."

He turned to face his staff. He had the glowing look of a boy about to skip school.

“Men, I’ll be back in a few hours. At that time we’ll discuss plans for withdrawing the Brigade and rejoining II Corp. In the meantime, send all the extra equipment some 10 miles to the rear. Also, get MacEye to finish boxing up that contraband so it can get sent to St. Louis. We’ll move the army at nightfall, tonight.”

Holmes leaped out of the cabin into the morning sunshine and danced and sang all the way to the riverbank. He passed groups of soldiers along the way who waved or called him by name. Even the birds came out of hiding and sensing this light hearted spirit, filled the air with song. With some sense of normalcy at last, the men sat down to eat their breakfast of sowbelly, hardtack, and coffee.

Once their commander had departed, the staff officers all breathed a sigh of relief. Now it was their task to prepare the army to march. The biggest challenge was dealing with the stuff in the barn.

The old barn was a short distance from the farmhouse and had been declared off limits to the soldiers. Even though the roof was sound and weatherproof, it was well guarded against trespassers for inside was contraband liberated by Union cavalrymen on a recent raid. The booty consisted of such things as tea sets, dinnerware, cutlery, cut glass brandy decanters, fancy candelabras, several ivory-handled combs and hairbrushes, fancy oil paintings, two chamber pots, and one brass tub big enough for to bathe a grown man.

If given a few more days, Lieutenant John MacEye could have done it, but no way could he box up all that crap before nightfall. MacEye was currently a supply officer, but had been a carpenter before the war therefore Samuel Holmes had volunteered him for this most crucial duty. But damn me if I can find proper lumber to build the boxes for this blamed contraband and stuff, MacEye silently fumed.

After hours of cursing to himself and pulling at his hair, he turned and shouted for the Sergeant Major. From the hayloft above him came a scraping of feet. A shower of loose hay fell the ground, followed by a pair of fat legs attached to a very large man. As he brushed the hay off himself, MacEye warily eyed the grinning ogre in the blue suit.

MacEye was a small round man of Nordic heritage. Both legs had been broken after a tragic tumble from a barstool and had refused to heal properly. Just under three feet tall, MacEye has to lean backwards to look up at the giant before him.

Sergeant Major Randy Rogers was a freak of nature, having been wounded many times and bearing the scars to prove it. But no wound was ever mortal, because Randy was encased in a layer of fat. He was a man as wide as he was tall with a heavy black beard matted with bits of old food. He must have been napping because when he yawned, he made a noise like a foghorn.

“Randy,” MacEye spoke softly and slowly so the giant would understand, “we need to get these valuables boxed up and shipped by this evening. However, I'm running out of proper wood and stuff. Please assign some men to forage for some building materials."

"Yes, loo tenant! I think I know just the men,” said Rogers as he put his paw to his cap in salute.

Some yards away, a group of blue coated men were huddled around a campfire. The flames didn’t put out much heat, so the men sipped from tin cups and prayed that the hot coffee would thaw out their bones. What had the men spellbound for the moment was not the hope of warmth, but the promise of a hot breakfast. In a long handled skillet, hunks of sowbelly were being fried. The owner of the skillet was bent over at the waist and used a fork to flip and turn the meat in its sizzling grease. Each man had been promised some of the fatback, so they were content to stand back with glazed eyes and wait. The drool that was running down their mouths made them look like rabid dogs.

Suddenly the arrival of the huge ape-like creature wakens the soldiers from of their trance. Sergeant Major Rogers had legs as thick as tree trunks and he stomped over to the campfire with the stride of a bull elephant. The soldiers felt the earth tremble. Rogers stopped before the blaze, unmindful of the smoke that whirled around his head, and swept his red piggish eyes back and forth.

With a wide grin, the soldier with the skillet unfolded himself and rose to his full height.

"Good mornin' Randy," exclaimed Higgy, a man who was as tall and thin as a washboard. Higgy had beady eyes set in a pinched face and a black handlebar mustache hanging under a long Roman nose. His uniform trousers and jacket were nearly worn out. Both had been patched a number of times, plus carried a variety of unidentifiable stains. The forage cap, atop a shock of black hair, might have been used to carry everything from garden vegetables to a bowel movement. E PLURIBUS UNUM was scrawled in the upturned brim of the cap. Overall, Higgy looked like the scarecrow that had just stepped out of a cornfield.

From a mouth a black as a cavern and with breath just a foul, the Sergeant Major spoke.

"Lt. MacEye is looking for some volunteers for a wood foraging detail and you're it," he declared, “I want you to take the Bagg's about three miles west to the village there, and bring back as much lumber as you can find. Hitch a mule to one of those wagon's from over yonder." He pointed toward the fence line where several were parked.

" I think there's some privy's you can knock down that should provide usable lumber."

“But, Randy. Why do we need to go into the village fer firewood? There’s plenty fine woods right here. Besides, I heard a feller say he heard wagon wheels and such moving during the evening. He says the sesech might try to circle us and get us from behind."

“The wood is for Lieutenant MacEye’s box building project,” the Sergeant Major growled, “Sam Holmes wants him to crate up all the contraband that was ‘liberated’ from on the last raid. As far as worrying about funny noises, that’s none of your affair. That’s for the officers to worry about. "

Rogers turned as if to walk away, but instead he spun around, snatched the skillet out of Higgy’s hand, and tipped the entire contents down his throat, hot grease and all.

“Now get those Bagg’s and get over to the village,” he barked, spewing grease all down his beard.

With a shrug of resignation and a sorrowful look back at his hungry comrades, Higgy walked about fifty paces to three gray, man shaped bundles. The men under these wool blankets were so tightly wrapped against the cold, only their snores escaped. Going from one to the other, he used the flat of his skillet on their backsides.

“Reach for the sky!”

Struggling out of their blankets were the brothers Charlie, Butthead, and Erik Bagg. The brother's were wearing the same blue uniform as the Union Army, but of a description similar to Higgy’s. Instead of a military cap, the brothers were each wearing a low crowned black hat with a very narrow brim. In the army, this type of hat was called a "pork pie."

Charlie was tall with a long, angular face, a high forehead and sad hound dog eyes. He ran bony fingers through hair the color of wheat. Butthead was of stockier material, thick limbed with a round Irish face. A quick smile and laughing angel eyes made him a favorite with the ladies. Erik, on the other hand, had a quick temper to match his fiery red hair and goatee. He was doing most of the cursing as Higgy explained the wood detail.

As the Bagg's shuffled over to where the wagons were parked, Higgy stepped over to where a gum blanket hung over four stacked muskets. Removing the rubberized canvas, which had kept the weather off the weapons during the night, Higgy examined the assortment of leather belts and straps that were slung over the bayonets of each musket. Cartridge boxes with slings, waist belts, wool covered canteens, and of course, tarred canvas haversacks. These were the soldiers 'traps', so called because once the soldier had these items on his body, he felt trapped in them.

Higgy took one of the haversacks and peered inside.

John Henry, you awake down there little one?"

Peeping up from within the tarred haversack was a little black rag doll made from lint and the scraps of old rags. Black strands of yarn on its head were long as the tentacles on an octopus. The doll wore a red flannel shirt, bib overalls, and no shoes. The rag doll blinked once or twice, rubbed sleep out of mother-of-pearl button eyes and in a tiny voice exclaimed.

“No mo’ rain, Higgy? I’se gets a bit chill’d las’ night.”

“Don’t fret, John Henry,” Higgy said in his calmest voice,“Looks like the cold weather is behind us. Being the naturalist I am, I ‘spect today will be hot.”

In a couple minutes the Bagg brothers came back, leading a swayback mule hitched to a wagon.

“Say Higgy, look what the cat coughed up,” announced one of the Bagg’s.

Lying in the bed of the wagon was a soldier curled up and fast asleep.

“Well feed me corn and watch me crow!” the doll John Henry exclaimed.

While Higgy and the Bagg's might have looked like an unmade bed, this unconscious newcomer was a P.T.Barnum curiosity. He wore the same blue uniform as the rest of the Union Army. Instead of the fatigue or sack coat, he had on a long tailed military frock coat - the sleeves of which were rolled to the elbow exposing a very loud red checked shirt. Plus, the coat was unbuttoned, revealing a green satin vest with glass buttons. An equally gaudy purple kerchief was knotted in a bow at his throat. A slightly dented Hardee Hat lay at his side. It was fully decorated with the brim turned up on one side and fastened by a pin holding a spectacular ostrich plume.

The soldier had nearly feminine features including a button nose, full red lips, and delicate cheekbones. The exception to near perfect features was the single black eyebrow that stretched across his forehead like a fat hairy caterpillar.

“Why its Dave Sullivan, the grossest boy in the Union Army,” Higgy said.

"Look's like he got himself some ‘popskull’," answered Charlie as he held up an empty champagne bottle, "Phoowee! Smells like he took a bath in the stuff."

"We can't let the Sergeant Major find him like this," said Higgy, "we'll just have to take him along with us and try to get him cleaned up."

The rifles and traps were laid in the back of the wagon and with a flick of the reins, the mule was urged westward carrying Higgy, the Bagg's, an unconscious Dave Sullivan, and the little rag doll John Henry.

No comments:

Post a Comment